Uzbekistan’s Gold-Based Wealth Growth Makes Its Economy Volatile

Soaring gold prices are stabilising Uzbekistan’s financial and economic base, yet risks of over-dependence are growing. A balanced domestic policy and integration into international mineral supply chains could see the commodity turbocharge President Mirziyoyev’s “New Uzbekistan” model.

Gold, Uzbekistan’s primary export, has unsurprisingly remained a mainstay of the domestic economy. The nation of over 37 million is experiencing a period of expansive economic growth that has been accelerated by a wide-ranging economic and financial liberalisation programme initiated by the President, Shavkat Mirziyoyev in 2016.

High gold prices, increased remittances from expatriate workers abroad, robust domestic demand and stronger investment trends will continue to drive the nation’s standout growth.

International instability drives gold price surge

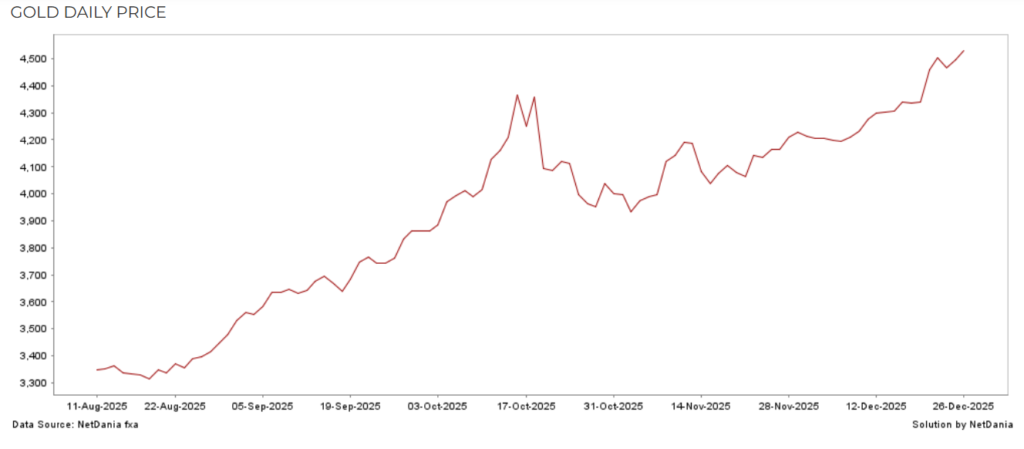

Gold, seen as a “safe haven” investment and a hedge against inflation, exchange rate depreciation, and falling revenues from bonds or other investments, has soared this year. The commodity has taken on an even greater role as nations grapple with high levels of international uncertainty.

Trying to predict and mitigate the risks of the ups and downs of Trump’s industrial policy remains a key challenge to global trade, while geopolitical tensions, namely in the South China Sea, Ukraine and in the Middle East continue to foster instability.

Gold momentum has also been catalyzed by factors related to the US Federal Reserve, including fears over the independence of the institution amid threats by President Trump to fire Chairman Jerome Powell earlier this year.

The Fed’s first rate since December 2024 in September, and expectations of further rate cuts well into 2026 have also driven gold up. However, the longevity of gold’s rally suggests that these factors are likely to have accelerated the growth in the value of the commodity, not directly caused it.

Despite high prices, central banks have returned to buying

Gold prices climbed from $3,857/oz on October 1st to $4,364/oz by October 21st. Despite a brief dip below $4,000 in November, the price has since risen to $4,489/oz. This represents a staggering 71% increase in 2025, building on a 41% rise in 2024.

Despite record prices, central banks resumed net gold purchases in August after a pause in July. Seven banks increased their holdings, led by Kazakhstan with 8t and China with 2t—the latter’s tenth consecutive month of buying.

Back in January, the Central Bank of Uzbekistan (CBU) topped the rankings for monthly gold acquisition, with a purchase of 8t. Buying activity remained robust in October, with the National Bank of Poland leading, resuming its purchasing activity with a 16t acquisition, taking total gold reserves to 531t.

Other buyers included Brazil, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ghana, Kazakhstan and the Philippines, with smaller purchases.

Multipolar ambitions from BRICS members are accelerating de-dollarization trends. Consequently, some nations are now replacing their dollar reserves with gold.

The increased use of sanctions by nations possessing powerful currencies such as Japan and the US has also stimulated a greater interest in bolstering gold reserves.

The Majority of the CBU’s reserves are held in gold

Gold is vital to Uzbekistan’s financial stability, helping the central bank hedge against external risks and default. This year, gross reserves grew from $41.2 billion to a record high of $61.2 billion by December 12th.

This puts Uzbekistan in a far greater position than regional peers, with reserves expected to easily cover 10 months of imports. Crucially, around US$50.9 billion of this total – or around 83% are held in gold.

Across 2025, the actual volume of gold assets has so far fallen marginally, with the increase driven by a jump in prices – not volume. A fifteen times increase in CBU-held securities has also helped to strengthen reserve assets.

Historically, the CBU enjoyed an exclusive right to purchase all domestically-produced gold. In 2019, this arrangement was replaced by a priority right giving the CBU first refusal on gold. This change was designed to strengthen legal processes and boost the nation’s investment framework.

The updated system allows greater access for smaller players in the jewelry industry, while maintaining a significant role for the CBU in the domestic market.

Higher gold prices also mean more government revenue to support President Mirziyoyev’s spending goals. Despite additional revenue, tax income remains volatile. This gold-driven success risks masking deeper inefficiencies in the tax system and the broader economy.

Increased revenue is welcome, but increased inflationary spending as a result could easily threatenthe government’s maximum 3% fiscal deficit goal for 2026.

The Uzbek som is strengthening alongside external and trade metrics

Historically weakened by inflation and devaluation, the Uzbek som gained ground against the dollar in the second half of the year. The currency strengthened by roughly 7% over the last 12 months, improving from 12,519 per dollar in April to 11,955 by December.

This stability is partly due to a weaker US dollar and rising foreign investment. Furthermore, increased remittances, high gold prices, and strategic gold purchases by the Central Bank have bolstered the som’s value.

In the first half of 2025, the current account deficit fell to $156 million, down from nearly $3 billion a year earlier. This decline was fueled by a 30% increase in exports and steady remittance inflows.

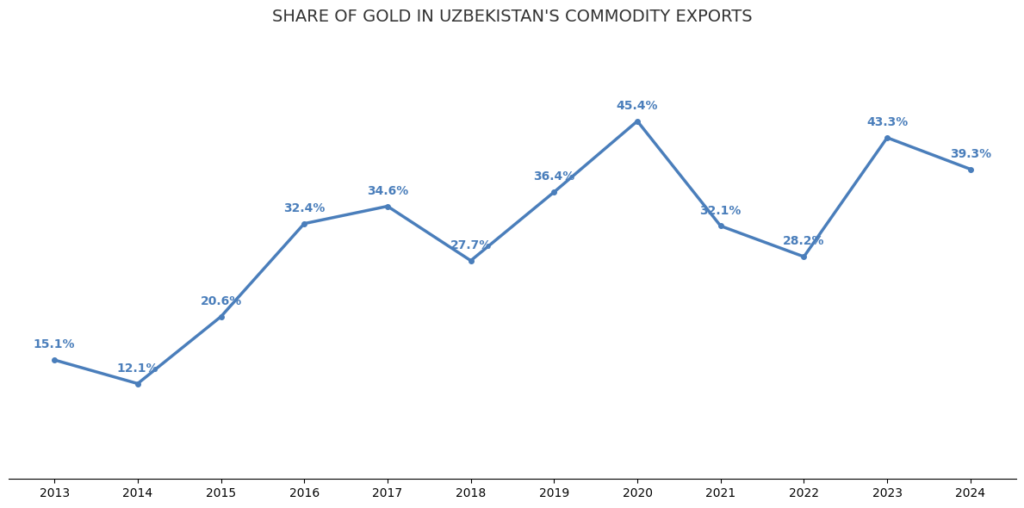

Gold now makes up more than 40% of total exports. However, because growth in non-gold sectors like services remains slow, this may not represent a long-term structural change.

Jobs, investment and domestic value-added manufacturing to boost growth

Alongside fiscal and external sector benefits, Uzbekistan’s gold bet is set to boost economic growth. With gold representing such a large percentage of exports, the nation’s key industry is weighing up plans for expansion.

Navoi Mining & Metallurgical Company (NMMC) operates on the of the largest open-pit gold mines in the world, the Muruntau deposit, located in the Kyzylkum Desert.

In 2024, the firm procured in excess of 3 million ounces – entering the world’s top five largest producers. The firm has boosted its output by around 32% since 2016.

NMMC’s expansion plans are among the most ambitious in the world. Backed by over $600 million in investment, the company aims to increase production by 30% by 2030. These funds will modernize technology and infrastructure to improve efficiency and develop new deposits.

Increasing gold sales to the jewelry industry will promote domestic manufacturing. Uzbekistan holds a competitive edge due to low production costs and strong government support.

These advantages allow the nation to boost production while remaining profitable. The metals sector contributed 6% to GDP in 2023, and this figure is expected to rise.

What to watch?

Record gold prices face risks from a stronger dollar and the end of the US government shutdown. However, gold demand remains high and is expected to grow through 2026. For Uzbekistan, gold is an economic mainstay, representing most reserves and over a third of exports. Yet, this overreliance creates a structural weakness, as price volatility could impact the whole economy.

To succeed, the government must develop the mineral value chain and capitalize on Central Asia’s role as a resource hub. By combining these efforts with market liberalizations, gold can act as a powerful engine for development. As Uzbekistan nears WTO accession in 2026, the government remains focused on the “New Uzbekistan” model.