The Kazakh Whetstone Sharpens the West’s Fight for Tungsten

The global crisis of 2022 did more than disrupt trade; it shattered the illusion of secure supply chains for the world’s most critical minerals. As sanctions silenced Russian mines and tightened China’s grip on the tungsten market, the West found itself at a dangerous crossroads.

Yet, in the heart of the Eurasian steppe, a massive new mining project is emerging to rewrite this narrative. Positioning itself as the West’s strategic tungsten partner, Kazakhstan is preparing to capture up to 15% of the global market, challenging Beijing’s long-standing monopoly and reshaping the geopolitics of the new ‘Great Game.

Kazakhstan Has Provided Trump With a “Whetting Stone”

The return of Donald Trump to the White House in 2025 gave fresh momentum to the global competition for critical minerals. The new U.S. administration identified strategic metals as a top foreign policy priority, shifting focus toward regions previously on the periphery of American interests. In the early months of his second term, Trump personally engaged in promoting resource deals, with a specific focus on Central Asia. Trump described the region as “incredibly wealthy,” arguing that the U.S. had previously undervalued its potential, allowing other players to dominate key segments.

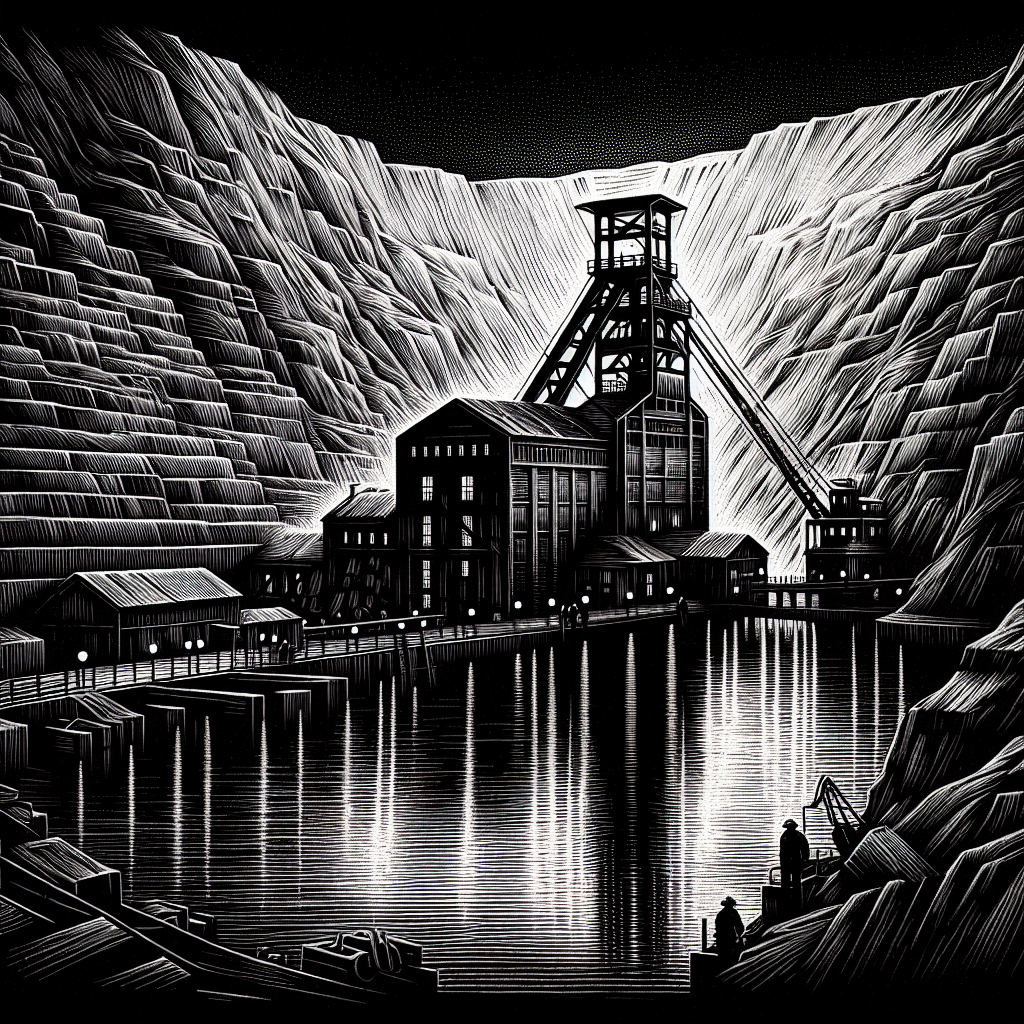

The most prominent example of this shift is the tungsten deal in Kazakhstan. In November 2025, during the C5+1 summit in Washington, agreements were announced for the joint development of the North Katpar and Upper Kairakty deposits in the Karaganda region. The resource base is estimated at 755 million tons of ore, containing roughly 854,000 tons of tungsten trioxide (WO₃).

Upper Kairakty is considered the largest tungsten deposit in the world, holding approximately 70% of all tungsten reserves in the former Soviet Union. Symbolically, the name Kairakty stems from the Kazakh word Qairaq, meaning “whetstone”—a reflection of the local geology.

As early as 2018, China’s Xiamen Tungsten expressed interest in the site, signing a preliminary memorandum. However, internal corporate disagreements prevented the project’s approval, and Beijing ultimately lost its grip on this world-class asset.

To execute the new deal, a joint venture was formed: the American firm Cove Capital holds 70%, while Kazakhstan’s national company, Tau-Ken Samruk, holds 30%. The project involves building mining and processing infrastructure with an initial output of 12,000 tons of tungsten per year—equivalent to 15% of current global production. With an estimated lifespan of over 50 years, Kazakhstan is positioned to become the world’s second-largest tungsten producer after China.

In 2025, the Kazakh government launched its largest geological mapping program in decades, investing $470 million into subsoil research. To date, Kazakhstan has identified 12 tungsten deposits with total reserves exceeding 2 million tons of WO₃.

Central Asia possesses vast, largely untapped reserves of tungsten, rare earth elements, copper, uranium, and antimony. Beyond Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan are also intensifying cooperation with Western investors. Uzbekistan is particularly promising, having already signed agreements with U.S. investors to develop rare earth elements. For these nations, this is an opportunity to diversify their economies, attract investment, and increase their geopolitical weight amidst the global restructuring of supply chains.

Beijing Seeks to Deny Rivals Access to Promising Deposits

China, which controls up to 83% of global production and roughly 52% of proven reserves, is monitoring these trends closely. For years, Beijing utilized price dumping and oversupply to keep global prices low, effectively driving international competitors out of business. This led to mine closures across several countries, including the U.S., cementing China’s status as a near-monopoly supplier.

However, as relations with the West soured, China shifted toward a more restrictive export policy. In 2023, it introduced licenses for several critical metals. By February 1, 2025, these measures were extended to tungsten, making exports contingent on special permits from the Ministry of Commerce. While not a formal ban, it creates significant risks of supply disruptions.

The market responded rapidly. In the first half of 2025, Chinese tungsten exports dropped by 24% year-on-year. By autumn, prices hit historic highs, with Ammonium Paratungstate (APT) exceeding $60,000 per ton. Shares of mining companies with deposits outside of China surged, and governments accelerated partnerships to develop new mines.

Faced with rising competition, Beijing has also intensified its external resource expansion to secure control over deposits in third countries. Chinese firms have shown interest in Vietnam’s massive Nui Phao complex. Furthermore, in late 2024, the “Zhetysu Tungsten” processing plant was launched in Kazakhstan with Chinese backing. With a capacity of 3.3 million tons of ore per year, the plant produces a 65% concentrate. The investor committed at least $450 million to the project; currently, 99.98% of Kazakhstan’s tungsten ores and concentrates are exported to China.

Essentially, Beijing is racing to either remain the primary supplier of high-value processed products or to buy out new sources of ore before Western competitors can develop them.

The Tungsten Race

The war in Ukraine stimulated a massive ramp-up in NATO arms production, driving demand for tungsten in munitions and military hardware. In 2023, G7 nations agreed on a mineral security plan aimed at diversifying supply sources. Leaders pledged to collectively counter unfair trade practices and market monopolization.

The United States has been particularly proactive. Between 2022 and 2024, Washington laid the groundwork to drastically reduce dependence on tungsten from “non-allied” nations. New regulations were approved requiring the American defense industrial base to completely phase out Russian and Chinese tungsten by 2027. In 2025 alone, the Pentagon planned to purchase over 2,000 tons of the metal. These steps are designed to build an alternative supply base outside of Beijing’s reach. Simultaneously, Canada’s Almonty Industries has accelerated the revival of the Sangdong mine in South Korea—once one of the world’s largest—specifically to meet U.S. demand.

What to watch

Despite these efforts, it is too early to speak of a truly multipolar tungsten market. China maintains dominant control over extraction, processing, and pricing, and the West will remain dependent on Chinese supply in the near term. Nevertheless, the market architecture is transforming. An alternative supply base is being built before our eyes.

For the business community, this signals new investment opportunities in Central Asian mining projects once considered too remote or risky. Today, these projects are on the front lines of the struggle for strategic resources and enjoy high-level political support. The battle for rare elements is intensifying; success will belong to those who can rapidly explore new deposits and forge mutually beneficial partnerships with resource holders. In Central Asia, such partnerships could yield significant economic dividends for the region and provide the world with a more stable, diversified system for critical materials.