Iran 2026: Managing Crisis in a Post-Legitimacy State

Iran has become a primary front in the Cold War between China and the United States. Both superpowers are maneuvering to secure conflicting interests. The regime’s coercive control currently prevents an open proxy war. However, its lack of domestic legitimacy has left the state in a dangerous stalemate.

Many contemporary theorists argue that authoritarian regimes rest on an implicit “social contract.” Under this deal, citizens tolerate limited rights and repression in exchange for security, basic welfare, and the promise of improvement. When this contract collapses, the regime enters a “legitimacy trap.” Formal channels for change remain blocked, but the population no longer accepts the existing rules of the game. The 2025–2026 Iranian protests illustrate this crisis. A society under heavy strain is now challenging a system that retains its coercive power but has lost its persuasive authority.

Recent actions by the U.S. administration indicate that regime change is not the actual goal in Iran; the primary objective is to weaken China’s allies. Chinese refineries had planned to increase their reliance on Iranian heavy crude. This move was intended to compensate for the loss of Venezuelan supplies. Iran also serves as a critical hub for China to bypass U.S.-controlled transport routes. These include the Strait of Malacca and the TRIPP route in the South Caucasus. Finally, the protests and U.S. support may weaken Iran’s hand in nuclear negotiations. These talks originally began in April 2025.

In late 2025, the rial crashed to record lows. The decline was fueled by new sanctions, austerity measures, and currency policy shifts. These rising prices provided an abrupt shock to already-strained households. Frustration soon boiled over into mass dissent. The movement began in the bazaars but quickly reached cities across the country, turning a currency crisis into a political one. This provides the U.S. with leverage through negotiation rather than intervention. By applying monetary pressure, the U.S. can test the regime’s willingness to make concessions.

External Pressure Helps the Current Regime Strengthen Its Narrative

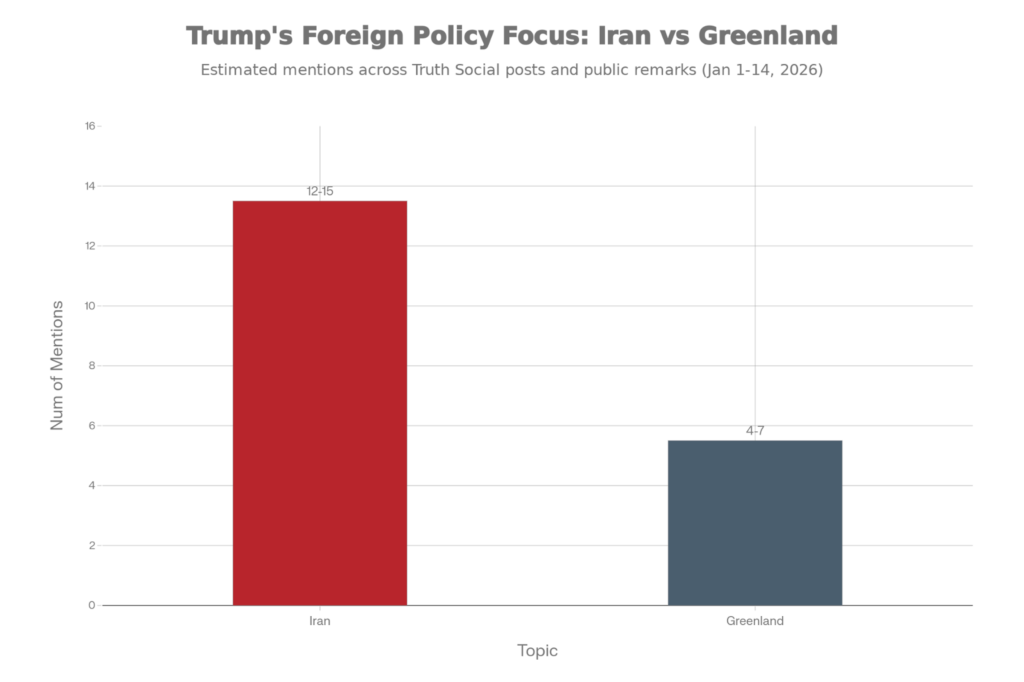

In this cycle, the external pressure on Iran is unusually sharp. Donald Trump has moved past sanctions to warn of ‘strong’ military action if mass killings occur. This shift frames domestic repression as a trigger for a U.S. response. Such statements are unprecedented in their directness. They signal that the cost of open bloodshed could now extend beyond Iran’s borders.

Inside Iran, this language is read ambivalently. Some segments of society view it as a possible deterrent against a repeat of earlier massacres. However, for many others, memories of Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan make any suggestion of intervention deeply unsettling. The authorities find the rhetoric politically useful. State media frames the unrest as foreign‑instigated and portrays protesters as instruments of U.S. and Israeli designs. This reinforces a siege narrative that helps justify crackdowns and maintain internal discipline.

Iran’s nuclear and missile programs amplify the stakes of any escalation. A direct U.S. or Israeli strike would carry significant regional risks. These include a wider conflict or the disruption of global energy flows. Such risks make governments cautious about linking support for protesters to military options.

Russia and China publicly oppose external interference and emphasize sovereignty. This stance aligns diplomatically with Tehran and constrains multilateral pressure for coercive measures. In practice, most external actors want to avoid outright state collapse or civil war. Paradoxically, this gives the regime space to repress. They can stay just below the threshold that would provoke decisive outside action.

Paths That Stop Short of Open War

There are several possible trajectories for Iran’s crisis. This helps explain how the regime can remain in power without sliding into full‑scale internal war.

- Repressive resilience. Authorities contain protests through calibrated force, targeted arrests, and intimidation. They can avoid the most visible mass killings that could unify the opposition or trigger external escalation. Protests subside from the streets but reappear episodically, while the legitimacy crisis continues to deepen beneath the surface. This path is precisely how the regime seeks to remain in power without crossing into the kind of systemic breakdown that would turn the country into an open battlefield.

- Escalation toward internal conflict. A more dangerous scenario would involve cracks within the elite and defections from the security forces. Armed resistance could also spread, particularly in border and minority regions where grievances are acute. In such a case, outside actors might be tempted to support different factions. This would raise the risk of a protracted proxy conflict, especially given Iran’s size, geography, and regional role. This fragmented, militarized struggle is exactly what observers mean when they speak of a “Syrian-style” outcome.

- Managed or semi‑managed transition. If key power centers conclude that the current model is unsustainable, they might attempt controlled adjustments. These could include limited constitutional changes or a redistribution of formal powers. They might even negotiate a change in leadership to protect their core interests while defusing pressure from below. For those inside the system, this path is not about democratization. Instead, it is about engineering a ‘soft landing’ to preserve the state’s integrity and avoid uncontrolled violence.

Across all three paths, the nuclear issue and regional entanglements act as both a shield and a trap for the regime. These factors deter straightforward external intervention. However, they also make any internal breakdown far more alarming to neighboring states and global powers.

Different Powerholders Frame the Situation Differently

The current wave is rooted in mounting economic pressures. These issues have become structural rather than temporary. Despite significant hydrocarbon resources, policy choices continue to prioritize the security establishment and regional proxies over broad-based welfare. High inflation and a weakening currency have fed a sense of injustice. Many ordinary Iranians feel they are paying the bill for elite interests and external adventures.

Protests centered on wages and resources tend to politicize quickly. Because institutional channels are closed, simple policy grievances soon become challenges to the political order. Reporting on the 2025–2026 unrest describes shuttered bazaars and heavily securitized city centers. Mobilization has spread beyond students to small towns and marginalized regions. So far, the leadership has chosen to tolerate these recurring waves. They prefer managing dissent over an all-out confrontation that could fracture the state’s own cohesion.

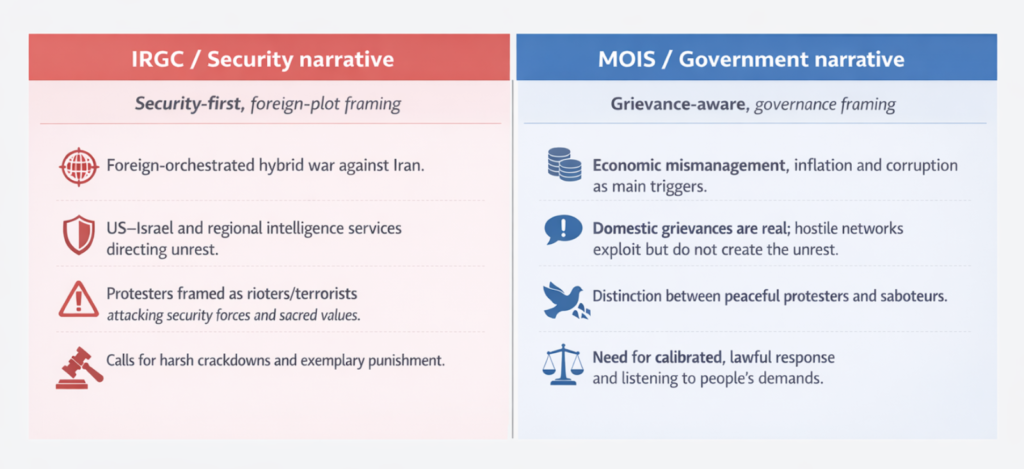

Iran’s pro-government media do not speak with a single voice. Instead, different security organs promote storylines that reflect their own institutional agendas. The IRGC (The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) frames the unrest as a foreign-orchestrated “hybrid war.” They cast demonstrators as terrorists attacking sacred values to justify harsh crackdowns.

By contrast, the MOIS (The Ministry of Intelligence and Security) and government camp blames economic mismanagement and corruption. They acknowledge domestic grievances but warn that hostile networks are exploiting the situation. This camp distinguishes between peaceful protesters and saboteurs. Consequently, they call for a calibrated, lawful response and occasionally suggest listening to the people’s demands.

Evolution of Protest Slogans Underlines Deepening Regime Delegitimation

One of the clearest indicators of deepening delegitimation is the evolution of protest slogans. Coverage of the current wave notes a shift from demands directed at specific governments or policies toward direct challenges to the supreme leadership and to the institutional foundations of the Islamic Republic. Traces of earlier reformist language still appear, but many chants now reject the governing framework as such rather than appeal to its self‑correction.

At the same time, the core of the early protests has frequently been non‑student groups: traders hit by currency collapse, workers and public‑sector employees facing wage erosion, and residents of peripheral regions suffering from neglect or environmental degradation. Student participation, while visible and symbolically powerful, has tended to follow rather than initiate the first outbreaks, reinforcing rather than originating the escalation of demands. This pattern underlines that the driving force is a broad erosion of socio‑economic expectations and confidence in the state, not a narrow generational revolt.

Lack of Clear Consensus Inside the Country on a Single Alternative Leadership Project

A notable development is the increasing visibility of exiled opposition figures, particularly Reza Pahlavi. Reporting has documented slogans explicitly invoking the Pahlavi name and coordinated calls from abroad that have been followed by mobilization in multiple cities, suggesting a degree of practical influence beyond the diaspora itself.

Yet public opinion inside Iran remains cautious. Many Iranians recall the trajectories of externally backed transitions elsewhere in the region and worry that any leader strongly associated with foreign support could undermine the legitimacy of political change or invite new forms of dependency. As a result, while exiled figures can serve as focal points for some segments and as interlocutors for international actors, there is no clear consensus inside the country around a single alternative leadership project. This ambiguity diminishes the likelihood of a rapid, leader‑driven collapse and instead favors a drawn‑out confrontation between diffuse societal dissent and a cohesive security state.