Ankara Finds Growth Points in Defense Cooperation with Central Asia

Türkiye is strengthening its influence in Central Asia’s defense sphere through drone exports, military training, and cooperation with Kazakhstan and neighboring countries.

The expansion of defense cooperation between Türkiye and the Central Asian states has drawn increasing attention in recent years and is often seen as a challenge to Russia’s dominant position in the region. High-profile initiatives launched by Ankara from drone production to joint military exercises cannot yet compare with the deep integration of Russia’s military-industrial complex (MIC) and its strong ties to many post-Soviet republics.

Türkiye is testing the waters to benefit from a forming vacuum as the Kremlin, under Western pressure, appears increasingly distracted and losing influence in key sectors across Central Asia from oil and gas to defense. This becomes particularly relevant given Türkiye’s growing military role in conflicts across the Middle East, the South Caucasus, and even Eastern Europe.

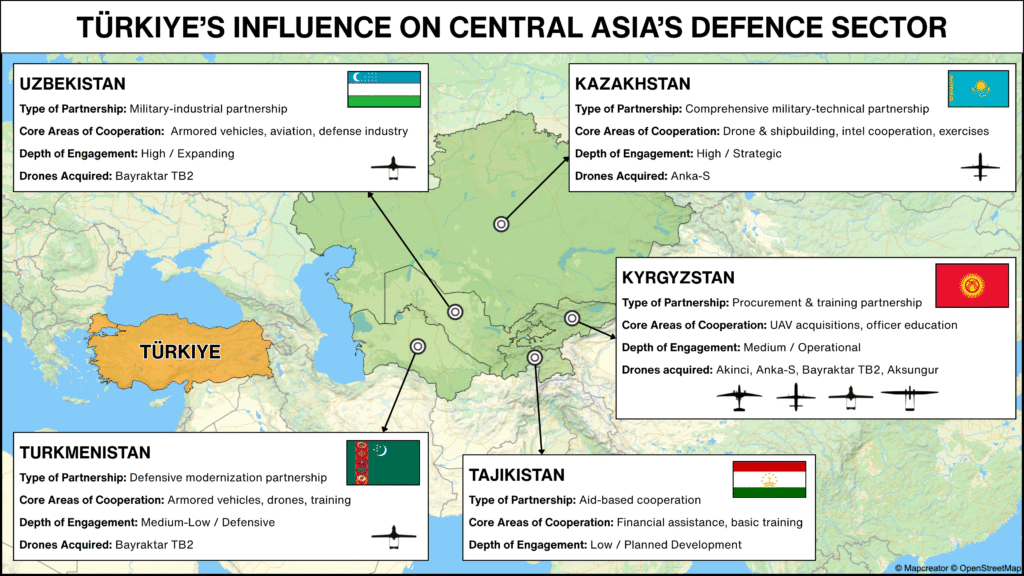

Türkiye is steadily expanding its defense footprint across Central Asia through drone exports, training programs, and joint production initiatives. While engagement levels vary by country, Ankara’s partnerships reflect a strategy of gradual influence rather than outright dominance.

Central Asia: A Growing Defense Market for Türkiye

Cultural and historical proximity gives Türkiye an important marketing advantage, which it uses strategically. Amid global instability, some countries in the region have begun to increase their defense spending, including the procurement of new military equipment.

However, given the modest size of Central Asian economies, the rise in defense spending remains relatively small by global standards. As a result, these countries tend to buy “cheap and targeted.” This makes Central Asia an increasingly important market for the Turkish defense industry. Ankara struggles to compete with major military corporations from the U.S. and Europe in established global markets, but it has been effective in capturing niche segments in the defense industries of Africa, the Middle East, and post-Soviet states.

Türkiye’s most successful company, ASELSAN, ranks only 54th among the world’s top 100 defense companies, according to the SIPRI Yearbook, with revenues of $2.56 billion in 2023, while U.S.-based Lockheed Martin, which tops the list, earned $67.57 billion.

The ranking is dominated by U.S. firms, 41 out of 100. Türkiye has only three companies on the list. The combined number of defense manufacturers outside NATO is smaller than the number of American companies: China – 9, Japan – 5, South Korea – 4, Israel – 3, India – 3, Russia – 2, Taiwan – 1, Singapore – 1, Ukraine – 1, and Saudi Arabia – 1.

For this reason, Western defense companies, unlike Ankara, do not view Central Asia as a promising market. Turkish arms in the region face competition from Russian, Chinese, Indian, Ukrainian, Israeli, and other non-NATO producers. Moreover, Central Asia is not transitioning to NATO standards, primarily due to the high costs such a transformation would entail.

Türkiye’s Niche: Affordable and Functional Systems

The use of Turkish systems should not be interpreted as a “turn to the West.” Türkiye offers affordable and effective products capable of competing in Central Asia’s defense markets. Notably, this applies to sectors such as drones, armored vehicles, and naval equipment. Furthermore, the development of Türkiye’s military-industrial complex shows positive trends, making export markets critically important.

Türkiye’s defense exports increased from $248 million in 2002 to $7.2 billion in 2024, while domestic production capacity reached 70% by 2024. Currently, Türkiye ranks 11th globally in terms of defense exports.

Ties Between Russia’s Military-Industrial Complex and Central Asia Cannot Be Broken Overnight

The historical connection between Russia’s military-industrial complex (MIC) and the Central Asian states, deeply rooted in the Soviet era, is hard to overestimate and even harder to dismantle quickly. The war in Ukraine has clearly demonstrated Central Asia’s “defense dependence” on Russia. According to Aigul Kuspan, Chair of the Committee on International Affairs, Defense, and Security of the Mazhilis (the lower house of Kazakhstan’s Parliament), “[In Kazakhstan’s army] the military equipment is outdated, and there is a shortage of ammunition. Due to sanctions, Russia has stopped supplying equipment.”

However, the Central Asian states are in no hurry to dilute their existing Soviet-based systems and technologies. According to The Military Balance 2023, the most diversified country in this regard is Turkmenistan, which experiments with foreign weapons and equipment, including those from Türkiye, which has been one of its largest suppliers. In 2021, Türkiye’s share in Turkmenistan’s arms imports reached 42%, mainly due to the sale of the C-92 frigate, although several experts argue that Italy remains Ashgabat’s main arms supplier.

This logic is understandable: even Turkmenistan retains dependence on Russia for weapon supplies that ensure its external security perimeter. In Turkmenistan, foreign arms are primarily used by internal security forces, while Soviet-made systems continue to dominate the external defense structure, just as in the rest of Central Asia.

If we examine Turkmenistan’s military imports, those from Türkiye include armored vehicles, drones, and patrol ships. Given Turkmenistan’s security context, the main external threat to the country originates from Afghanistan. For this reason, the officially neutral state that avoids membership in military-political blocs strengthened its cooperation with Uzbekistan in 2015 to secure the Turkmen-Afghan border.

Turkmenistan shares the longest land border with Afghanistan, stretching approximately 804 kilometers across the provinces of Herat, Badghis, Faryab, Jowzjan, and Balkh. The map highlights key border regions and Turkmen population concentrations within northern Afghanistan. Source: Public Intelligence .

The Turkmen-Afghan border is the longest land border with Afghanistan among Central Asian countries, and its protection is complicated by the desert terrain. This requires equipment that enables rapid mobility and effective border monitoring, capabilities provided by armored vehicles and drones.

These same systems are also crucial for urban operations, which would be the most likely scenario in case of attacks from non-state actors such as terrorist groups. These threats are the most probable if we consider risks emanating from Afghan territory.

From Russia, Turkmenistan imports traditional Soviet-designed weaponry such as tanks, multiple rocket launch systems (MLRS), infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs), and helicopters. This again underscores that even the relatively diversified Turkmenistan remains dependent on the Russian or Soviet MIC.

It follows that Turkish systems are filling a niche in Central Asia that was not previously considered tactically significant by Russia’s armed forces until the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Türkiye’s defense products have found demand particularly in the segment of “strike (combat) drones,” bolstered by their recent success during Azerbaijan’s Nagorno-Karabakh operations and Ukraine’s defense efforts in 2022. Nevertheless, Turkish drones are far from dominant in the Central Asian market, which has already tested drones from China, Israel, Pakistan, and other states.

It is also worth noting the statement by Colonel Vadym Valiukh, commander of Ukraine’s Main Intelligence Directorate (GUR), who said he is “not inclined to use the word ‘useless’” to describe the TB2 Bayraktar drones but admitted that they are now difficult to deploy effectively. “At the beginning of the war, they were used more frequently and inflicted more damage on the enemy. But Russian air defense and electronic warfare systems have adapted. The last TB2 flight lasted only 30 minutes,” he noted.

Central Asian countries are taking a cautious approach in adopting foreign military systems, which generally complement but do not replace their core combat capabilities. Across the region, the foundational firepower on land (tanks, artillery, air defense), at sea, and in the air still relies on Soviet-origin systems. Finally, three out of five Central Asian countries are members of the CSTO, and as representatives of Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Defense have stated, “The interoperability requirements for CSTO-compatible weaponry remain in place. At the same time, the CSTO is exploring cooperation with non-member states.”

Myths About Türkiye’s Military Influence in Central Asia That Irritate the Kremlin

Engagement with Türkiye is acceptable for the Central Asian countries, as it does not provoke direct confrontation with Russia, which views Türkiye as a “complex partner” for both the Kremlin and Washington, as well as for other rivals. Türkiye, much like Kazakhstan and other countries in the region, plays an important “mediating role” between the West and the East. Cooperation between intermediaries is traditionally not considered problematic between opposing blocs but rather encouraged by both sides. However, there are also challenges, specifically narratives that create myths around Türkiye’s military influence in Central Asia.

One of these narratives claims that “Türkiye is pushing Russia out of its traditional sphere of influence,” a theme repeatedly circulated by pro-Russian Telegram channels for several years. Yet many arguments about Türkiye’s alleged military dominance in the region are exaggerated, and several examples prove this.

For instance, media outlets widely circulated a story about Türkiye’s supposed “dominance” in the Caspian Sea. In 2023, several outlets falsely reported that Türkiye planned to build warships for Kazakhstan’s Navy. The reports claimed that Kazakhstan’s Zenit plant had signed a contract with Turkish defense companies ASFAT and YDA Group to construct ships for Kazakhstan’s Navy. Although this story was quickly refuted, it continued to circulate within some analytical circles, to the point that even reputable commentators began warning of Türkiye’s impending “domination” in the Caspian, a narrative that ignored the established status quo.

Despite the fact that this news was officially denied on July 31, some experts continued to believe that Türkiye would build warships for Kazakhstan. In reality, the Russian Navy remains the largest and most powerful naval force in the Caspian Sea basin.

Another issue that continues to irritate the Russian expert community is the topic of Turkish drones in Central Asia. Indeed, “drone diplomacy” has become a hallmark of Türkiye’s strategy in the region, with even Tajikistan planning to purchase Turkish UAVs. All other Central Asian countries have already acquired Turkish drones, though of different models. Kazakhstan even announced plans to launch the production of Turkish ANKA drones by Turkish Aerospace on its territory as early as 2022, aiming to become the first country in the world to do so. Yet this project faced delays. The production was expected to begin in 2024, but this did not happen.

The Turkish Aerospace project remains at a preliminary stage, as due diligence continues regarding investments and infrastructure requirements. Although Turkish Aerospace Limited, a subsidiary of the company, was registered in Kazakhstan and began paying taxes, the promised ANKA production line has not yet materialized. By the end of 2024, it became known that Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Defense and Baykar Defense had reached an agreement to establish Bayraktar drone production within Kazakhstan.

The delays highlight the complexity of fully localizing advanced drone manufacturing and the delicate balancing act between Kazakhstan and Türkiye. Both sides must ensure that the project aligns with Kazakhstan’s long-term defense modernization goals without jeopardizing its relations with Russia or the CSTO. Moreover, launching drone production, even if it is limited to assembly and maintenance, requires building a complete supply chain, since Turkish drones contain many imported components from European and North American countries.

If and when production begins, it is expected to remain fully under Kazakhstan’s control. The technologies will be owned locally and could potentially be integrated into exercises with CSTO partners and other strategic allies.

This section can be concluded with another recent story that caused confusion among Russian analysts: reports of joint military exercises supposedly held under the auspices of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). In reality, not all OTS members participated, and the drills were conducted as part of the 21st operational course on counterterrorism in urban environments, not under the OTS framework. Meanwhile, Russian analysts overlooked another point: Kazakhstan had planned to hold joint exercises with Türkiye called Qabylan Joly-2024, which ultimately did not take place.

Overall, at this stage, Türkiye’s military approach to the region does not imply any form of institutionalization.

Five States, Five Directions of Türkiye’s Military Diplomacy — and the Organization of Turkic States Has Nothing to Do With It

An analysis of 35 years of Türkiye’s engagement with the Central Asian states shows that no unified approach to military cooperation with the region has yet emerged. This can be explained by a variety of factors, but most importantly by the differing needs of each country due to their individual characteristics.

As shown earlier, analyses of military cooperation between Central Asian countries and Türkiye (and even Azerbaijan) often invoke the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). In reality, the OTS, in its current form, does not prioritize collective military initiatives. Its strategic plan, Vision of the Turkic World 2040, does not mention defense integration, reflecting the fact that both Russia and China would be uncomfortable with any security structures resembling NATO in their near abroad. While Ankara and Baku may seek to institutionalize defense cooperation within a Turkic framework in the long term, this ambition has not yet materialized and remains politically sensitive for now.

It is important to note that three of the five Central Asian states participate in military exercises on Turkish soil, known as “Efes” and “Kış.” These exercises typically focus on specialized training and niche capabilities. Such engagements allow Central Asian militaries to test new operational approaches while maintaining their cooperation within the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), preserving existing structures and exploring additional avenues for capacity building.

CSTO exercises, which often involve thousands of soldiers and complex peacekeeping operations, underscore the enduring multilateral security mechanisms that anchor the region. In short, Türkiye’s initiatives add diversity but do not displace the central role of CSTO drills and cooperation with Russia in shaping the region’s defense posture.

For this reason, Türkiye and the Central Asian countries emphasize the development of bilateral cooperation programs, signing corresponding agreements at the ministerial level. The approaches of each country can be summarized as follows:

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has the most diverse range of military cooperation with Türkiye. As noted earlier, Kazakhstan is expected to host the production of Anka drones—the first such project outside Türkiye. The two countries have also signed a protocol on cooperation in military intelligence, which, unlike a similar agreement with Azerbaijan, mainly regulates information exchange and threat monitoring.

Both documents frequently appear in Russian Telegram channels, although they often omit mention of the Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Kazakhstan on Military Cooperation dated October 16, 2020. Article 8, paragraph 2, of that agreement states: “Each Party undertakes not to conduct intelligence activities directed against the other Party.”

Türkiye and Kazakhstan are also exploring a unique area of cooperation—joint shipbuilding. It remains unclear whether this involves military vessels, but there are certain indicators. The registration of DEARSAN BAUTINO SHIPYARD LTD in Kazakhstan coincided with announcements about the construction of a $250 million shipyard included in the investment portfolio of Kazakh Invest. The same company, as part of a joint venture, built 10 Serhet-class patrol boats for the Turkmen Navy over the past decade.

However, economic and geographic realities suggest that the project will lead to limited results rather than a transformation of Kazakhstan’s maritime industrial base. Bautino, located in the Mangystau region of Kazakhstan, primarily serves as a hub for oil and commercial fleets rather than a site suitable for advanced naval construction.

Given Kazakhstan’s focus on developing domestic enterprises such as Zenit JSC and Hydropribor Research Institute JSC, Türkiye’s role is likely to be complementary, perhaps centered on small military boats or dual-use civilian vessels, rather than creating a new dominant naval presence.

Uzbekistan

Military-technical cooperation between Uzbekistan and Türkiye gained momentum in 2016 following President Erdoğan’s visit to Tashkent, with President Mirziyoyev’s reciprocal visit in 2017 elevating relations to a level of comprehensive strategic partnership. The legal foundation for this cooperation was established through key agreements in 2022 on military-technical collaboration and protocols on military education signed in 2020.

The most notable example of military-technical cooperation is the project for producing Ejder Yalçın armored vehicles. In October 2017, the Turkish company Nurol Makina signed a memorandum of understanding with the Uzbek enterprise UzAuto, providing for the production of 1,000 armored vehicles. The first phase involved the delivery of 24 finished units, successfully completed in 2019. These vehicles were produced in Türkiye, and there is currently no public information about local assembly in Uzbekistan.

In December 2023, Uzbekistan ratified the Agreement on Cooperation in the Defense Industry between the two countries. By 2024, defense cooperation continued to deepen, with a key milestone being President Mirziyoyev’s visit to Turkish Aerospace Industries, where prospects for collaboration in the aviation sector were discussed.

Kyrgyzstan

Military cooperation between Kyrgyzstan and Türkiye began in 1993 with the signing of an agreement on military education. The key documents that shaped the partnership were the Treaty on Eternal Friendship and Cooperation (1997) and the Agreement on the Establishment of the High-Level Strategic Cooperation Council (2012). Kyrgyzstan became the first CSTO member state to acquire a full range of Turkish UAVs, including the Bayraktar TB2, Akıncı, ANKA, and Aksungur. It is the second country in the world after Türkiye to operate all four drone models produced by the Turkish defense industry.

Since 1993, more than 300 Kyrgyz officers and about 100 cadets have been trained in Turkish military institutions. As researchers note, the nature of cooperation has shifted in recent years from traditional non-reimbursable aid to commercial arms procurement deals.

Turkmenistan

Most areas of cooperation between Turkmenistan and Türkiye have already been outlined, but it is worth noting that military collaboration continues to develop in accordance with Turkmenistan’s neutral status and remains strictly defensive in nature. This means Turkmenistan does not participate in any joint military exercises at all, except with Russia and Uzbekistan, according to The Military Balance 2024.

Turkmen military personnel regularly undergo training in Türkiye to enhance their professional skills, study advanced military methods, and exchange experience on modernizing logistics and infrastructure.

In 2024, the partnership received new momentum. In June, Turkish Defense Minister Yaşar Güler visited Ashgabat, where discussions focused on strengthening cooperation in defense, modernizing Turkmenistan’s military-technical base, and introducing new technologies. Both sides expressed their intention to expand collaboration in areas such as digital technologies, the further modernization of Turkmenistan’s armed forces, and the expansion of programs for training military specialists.

Tajikistan

In April 2022, the defense ministers of Tajikistan and Türkiye signed a framework agreement on military cooperation. In July 2023, the two countries concluded a new defense cooperation agreement and a financial assistance protocol. Under this assistance package, Türkiye planned to allocate 50 million Turkish lira ($1.5 million) to Tajikistan for the purchase of Turkish military equipment, as well as 2 million lira ($62,000) for the training of Tajik servicemen in Turkish military academies. The Tajik parliament ratified the defense cooperation agreement, making it likely that both sides will begin implementation in 2025.

Summary

Türkiye’s military cooperation with the Central Asian countries is evolving along individual trajectories, taking into account the specific characteristics of each state. Despite the existence of the Organization of Turkic States, military integration is not among its priorities, and cooperation is built primarily on a bilateral basis:

- Kazakhstan demonstrates the most diversified cooperation, including drone production and shipbuilding development.

- Uzbekistan is expanding military-technical cooperation, especially in armored vehicle and aviation manufacturing.

- Kyrgyzstan became the first CSTO member to acquire Türkiye’s full UAV lineup and continues to strengthen military education ties.

- Turkmenistan develops cooperation in line with its neutral status, focusing on defensive aspects.

- Tajikistan is in the early stages of defense cooperation with Türkiye, developing it through financial aid and military training programs.

It is important to note that Türkiye’s military presence in the region does not replace but rather complements the existing security structures, primarily those linked to Russia and the CSTO.

Incremental Influence, Not Radical Change

Türkiye’s military-diplomatic engagement in Central Asia, and particularly in Kazakhstan, highlights Ankara’s ambition to expand its regional footprint. However, the notion that Türkiye is poised to replace Russia’s role in the Central Asian military-industrial complex is greatly overstated. While Turkish technologies, especially drones, can fill specific niches and introduce new standards, the region’s deep structural ties with Russia, its continued dependence on Soviet-era stockpiles, and the cautious approach of local governments mean that Ankara’s influence will remain limited.

Misinterpretations by media outlets and analysts often fuel inflated expectations of Turkish dominance. In reality, Türkiye’s defense initiatives, though significant, operate within a constrained environment shaped by regional power balances, long-standing ties with Russia, and the strategic prudence of Central Asian leaders. In this evolving landscape, Türkiye is likely to remain a complementary partner rather than a transformative actor in Central Asia’s defense sphere.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally written and published in Russian on the Kazakh platform Cronos.asia on July 21, 2025.