China’s new soft power model focuses on vocational training in Central Asia

On November 21, 2023, Kyrgyzstan signed a five-party agreement with Chinese universities and construction companies to establish the first Luban Workshop in Bishkek.

By October 2024, the center was already operational, featuring three “smart” classrooms and 14 laboratories equipped with approximately $1 million worth of machinery provided by China. Plans are also underway to open a second center in Osh.

By September 2025, such workshops had appeared in all five Central Asian countries, evolving from isolated projects into a coordinated regional system.

Through this initiative, Beijing is directly embedding its technical standards into the region’s labor markets, transforming traditional soft power into a form of structural influence.

China adapts its soft power

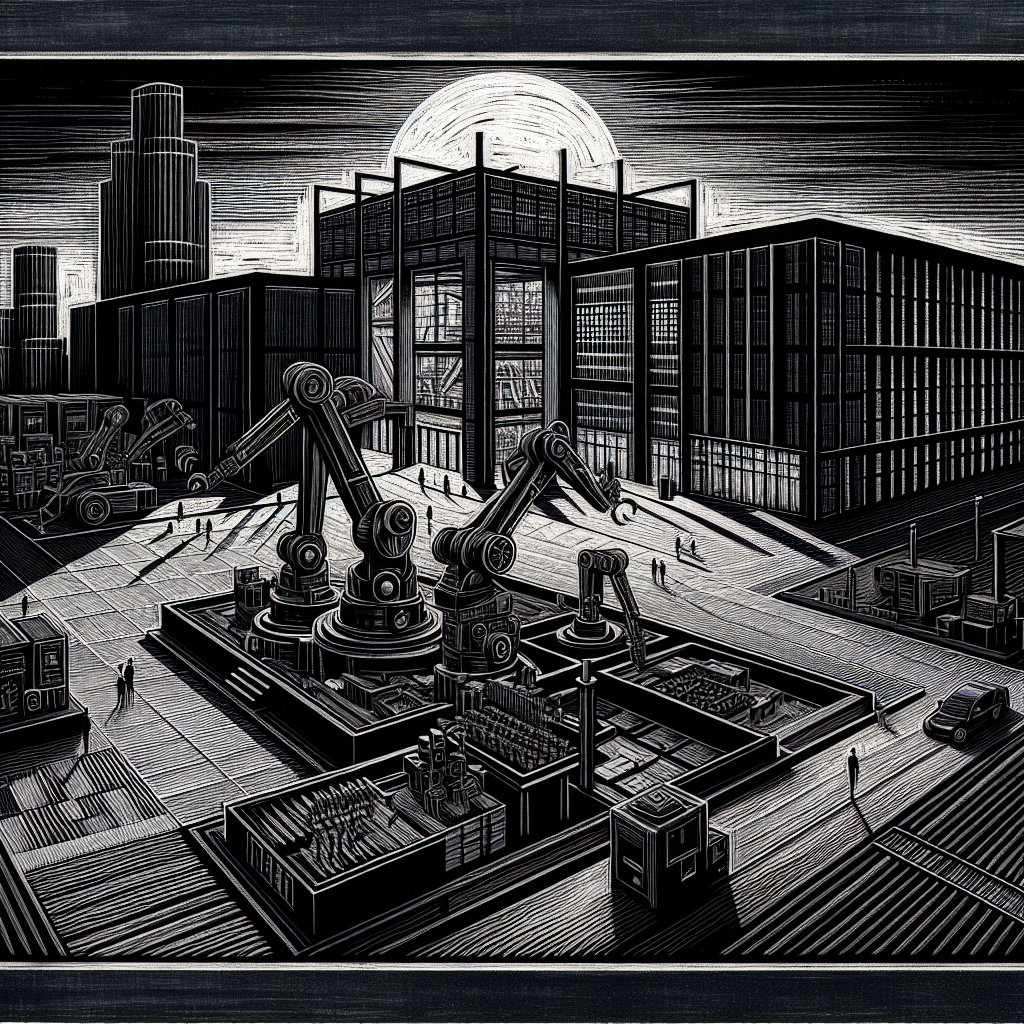

These workshops provide practical training in robotics, hydrodynamics, intelligent energy systems, and IT.

Most graduates are expected to find employment within “Belt and Road” projects, including the construction and operation of the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway.

This approach differs significantly from that of the Confucius Institutes: while language and cultural programs build a positive image of China, vocational-technical centers create tangible dependencies.

In 2023 alone, 5,986 Chinese vocational courses were implemented abroad.

For Beijing, this ensures the availability of a “compatible” talent pool, strengthens political trust, and accelerates the expansion of the Chinese industrial ecosystem.

The expansion of this program coincides with a reduction in similar initiatives from the US and the EU. China is filling this vacuum with a model that bets on employment rather than culture—directly linking young specialists to Chinese companies or joint ventures operating under Chinese standards.

Benefit and dependency

For Kyrgyzstan, the benefits are clear: access to modern laboratories, a reduction in youth unemployment, and opportunities for international exchange.

However, the training is closely tied to Chinese equipment and curricula, which may limit the adaptability of graduates to alternative systems. Over time, educational norms and methodologies may shift as Chinese standards become more deeply rooted.

The region gains modern education and technology, but a key question arises: how can Central Asian governments balance local labor market needs with Chinese investments in vocational education while ensuring compliance with both national and international standards?

While the EU once emphasized academic mobility and the US focused on humanitarian education, China is offering direct employment pipelines. The result is influence that penetrates deeper into economic structures than traditional cultural diplomacy.

Luban Workshops provide China not only with a trained workforce for infrastructure projects but also with long-term positions in shaping the region’s institutional landscape.

These centers could become an opportunity for Central Asian countries—if they can use them as a foundation for developing their own vocational-technical systems, integrating diverse international standards, and aligning education with national development goals.