Central Asian Capitals Risk a “Tehran Moment” Without Urgent Water Reform

As Tehran’s water reservoirs near dead storage and its government considers evacuation plans for parts of the capital, a slow collapse is unfolding that offers a stark warning for Eurasia. While Central Asia has not yet reached the “Day Zero” that threatened Cape Town in 2018 or the chronic crisis afflicting Mexico City, the trajectory is unmistakable. Mismanagement, climate stress, and institutional weaknesses are pushing the region toward a dangerous threshold.

The honest assessment is that the region is not there yet. However, without decisive action to modernize water infrastructure and govern shared rivers cooperatively, Central Asia’s megacities, Tashkent, Bishkek, Almaty, Astana, and Dushanbe, could find themselves drifting toward the same irreversible crisis.

Glacial melt and agricultural waste deplete shared resources

Central Asia’s water future has always been precarious, relying on the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers fed by the Pamir and Tien Shan mountain systems. These ranges are warming significantly faster than the global average. Glaciers have already lost a large share of their mass since the 1960s, and hydrological projections indicate that flows will become increasingly erratic as warming accelerates.

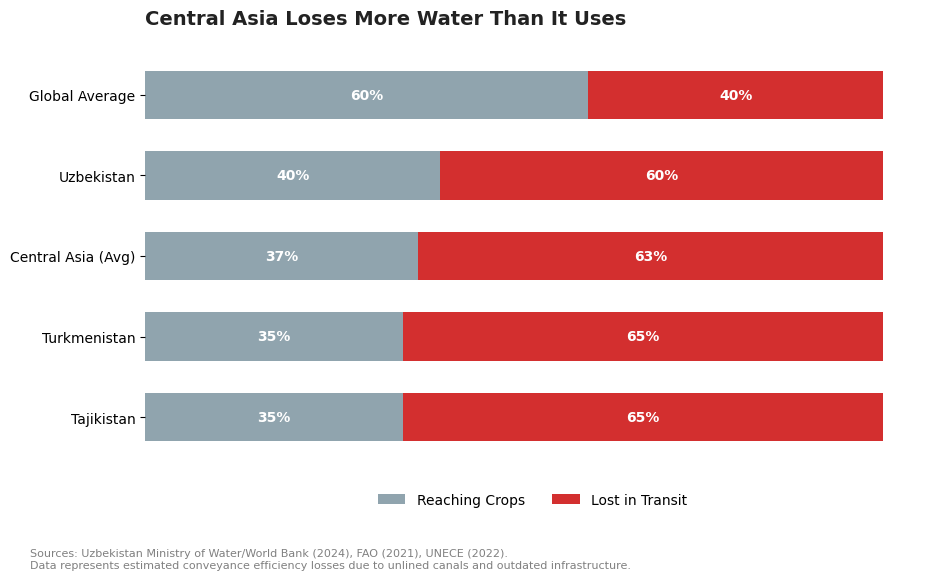

Despite shrinking supplies, the region consumes water with astonishing inefficiency. Agriculture remains the dominant user, accounting for approximately 80 to 90 percent of total withdrawals. The sector relies on gravity-fed, open-canal irrigation systems that lose enormous volumes to seepage and evaporation. In some districts, up to 40 percent of irrigation water disappears before reaching the fields.

The result is a paradox: countries that once considered themselves water-rich now face growing shortages, deteriorating aquifers, salinized soils, and shrinking wetlands. While currently most visible in the Aral Sea basin, these symptoms foreshadow a broader urban crisis.

Aging infrastructure and high consumption expose capital cities

Tashkent and Bishkek do not currently experience the acute stress of Tehran. Yet, both capitals are far more vulnerable than they appear. Much of the water infrastructure dates back to the Soviet era and has been maintained through emergency repairs rather than systematic replacement. In Bishkek, aging segments of the network regularly burst, flooding streets and draining reservoirs.

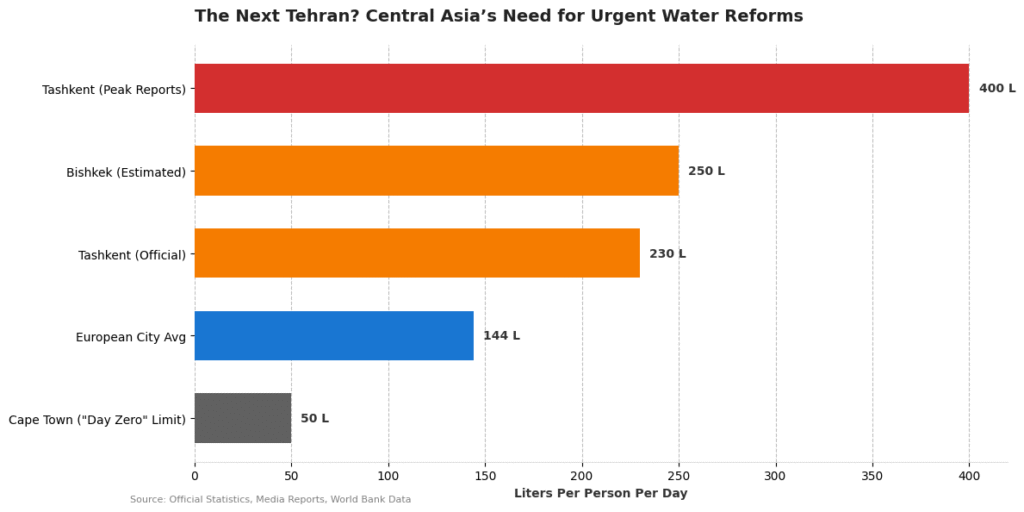

Data on consumption levels reveals a critical vulnerability. In Tashkent, official figures show daily residential water use of 230–270 liters per person, with reports of peaks reaching 400 liters per capita per day. The city’s “norm” for unmetered apartments stands at a staggering 350 liters.

The chart compares daily water consumption per capita. Tashkent’s usage significantly exceeds the 100–200 liter average typical of Western cities, highlighting the urgent need for demand management.

These figures place Central Asian capitals on a fragile footing. Even before the climate crisis worsens shortages, the combination of high usage and leaking infrastructure makes cities like Tashkent, Bishkek, and Dushanbe highly susceptible to supply disruptions.

Governance failures and data gaps hinder effective management

Technical inefficiencies are symptomatic of a deeper governance problem. The region relies on allocation systems designed in the Soviet era, systems that assumed predictable glacial flows and centrally planned cropping patterns that no longer exist. Water agencies remain underfunded and politically weaker than agricultural or energy ministries.

Furthermore, tariffs do not reflect the actual cost of service, leaving utilities unable to fund basic maintenance. This is compounded by significant data gaps. Real-time information on withdrawals, flows, and storage is uneven, making transparent monitoring and equitable management nearly impossible.

The Qosh Tepa Canal introduces a new strategic uncertainty

Regional water politics are shifting rapidly as Afghanistan accelerates construction of the Qosh Tepa Canal. With Phase 1 complete and Phase 2 excavation exceeding 90 percent, Afghan authorities indicate the project could be fully operational by 2026, two years ahead of the original 2028 target. The 285-kilometer canal is designed to divert approximately 6–10 cubic kilometers of water annually, roughly one-third of the Amu Darya’s flow, to irrigate northern Afghanistan.

The impact is no longer theoretical. In Uzbekistan’s southern Surxondaryo region, local officials report that flows into the Amu-Zang canal have already plummeted from 75 to 48 cubic meters per second since construction began. This sharp decline has forced the abandonment of vineyards in districts like Termez and Sherobod, driving rural labor migration and compounding a decade-long 16.7 percent decline in regional water availability.

The geopolitical fallout has widened significantly in 2025. While Turkmenistan faces potential losses of up to 80 percent of its intake, Kazakhstan has joined its neighbors in warning of a cascade effect. Astana fears that as Uzbekistan loses Amu Darya water, it will compensate by drawing heavily from the Syr Darya, potentially cutting Kazakhstan’s supply by 30–40 percent. This transforms the canal from a localized dispute into a pan-regional security crisis, making a cooperative framework with Kabul a strategic necessity.

A dry winter exposes the fragility of the energy-water nexus

The region is entering the 2025 winter with a severe precipitation deficit, creating an immediate crisis that foreshadows future scarcity. National hydromet agencies report that autumn and early winter were 40–70 percent drier than normal. In Khujand, the situation is dire enough that communities have begun offering public prayers for rain.

The consequences are already visible in the energy sector. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan rely on hydropower for over 80 percent of their electricity. With reservoirs shrinking, rural Tajikistan is currently restricted to just two to three hours of electricity per day. This is not an anomaly but the new climate reality; the World Bank warns river flows could drop another 20–30 percent by 2035.

The lack of precipitation has also worsened environmental health. Without rain to clear the air, dust storms and trapped pollution have pushed Air Quality Indices (AQI) in Dushanbe and Khujand to “unhealthy” levels. Furthermore, the low snowpack threatens spring irrigation, increasing the likelihood of harvest failures and rising food prices.

Unchecked scarcity will trigger migration and regional instability

Failure to act will set off a chain reaction with profound geopolitical consequences. As salinization spreads and yields decline, rural households in the Fergana Valley, Khatlon, Sughd, and drought-prone districts of Kazakhstan will face shrinking incomes. This will accelerate climate-induced migration, not as a single dramatic wave, but as a steady exodus toward provincial capitals and major cities.

As populations concentrate in cities with already overstretched systems, the pressure on municipal authorities will surge. Water rationing and rotating cuts could inflame local grievances and erode trust in government, a dynamic already visible in parts of the Middle East and South Africa. In a region where borders and enclaves remain sensitive, competition over water risks amplifying long-standing tensions between upstream and downstream states.

What should be done now?

- Reform water and energy efficiency (losses in water networks reach 40–70%; grid losses among the highest in Eurasia).

- Scale solar, wind, and biogas — hydropower alone is no longer reliable.

- Stop uncontrolled high-rise construction that overwhelms water and power systems.

- Move cement and coal-based industries away from cities to cut pollution.

Outlook

The region has a narrowing window to prevent water from becoming a source of instability. Avoiding Central Asia’s “Tehran moment” requires a shift from political commitments to implementation. A sustainable future demands large-scale modernization of irrigation (drip and sprinkler technologies), the introduction of realistic water pricing, and the strengthening of institutions like IFAS.

Simultaneously, the region must establish a structured water dialogue with Afghanistan to manage the impact of the Qosh Tepa Canal. Water crises do not erupt overnight; they build slowly before overwhelming the system. Central Asia can still rewrite this story, but only if efficiency and cooperative governance become immediate national priorities.