Central Asia Makes Uranium the New Arena of Great-Power Competition

Central Asia occupies a uniquely important position in the global uranium market, combining large geological endowments with a long, and often traumatic, history of extraction. In absolute terms, the region holds one of the world’s largest concentrations of economically recoverable uranium.

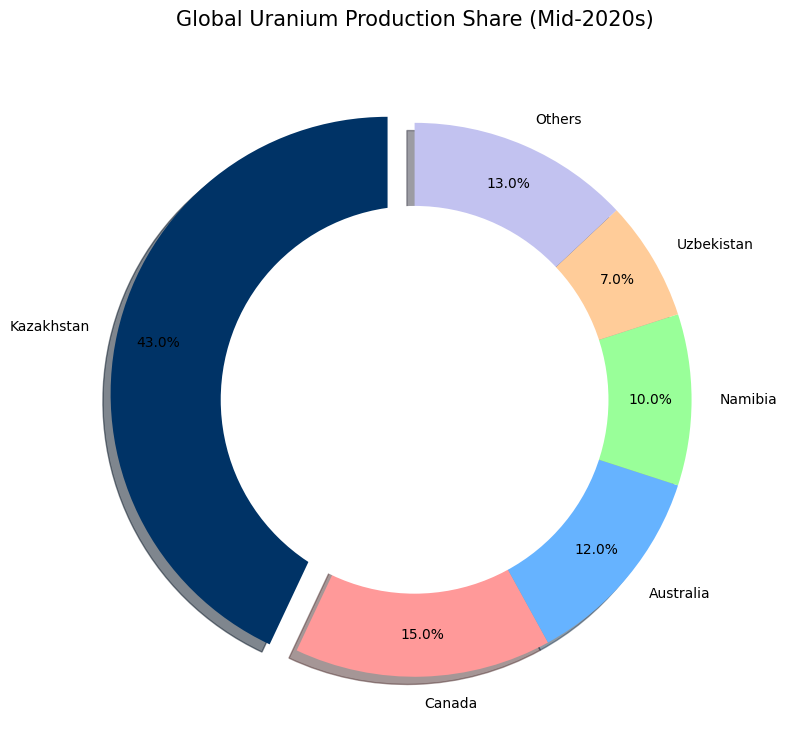

Kazakhstan alone accounts for roughly 12–15 percent of known global uranium resources and produces about 40 percent of annual global uranium output, making it the undisputed backbone of world supply.

Uzbekistan ranks among the top ten producers globally and holds the second-largest uranium reserves in the post-Soviet space after Kazakhstan. Smaller but geopolitically and environmentally significant deposits are found in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, largely as a legacy of Soviet-era exploration.

Historically, Central Asia was integral to the Soviet nuclear-industrial complex. Uranium mining was pursued with little regard for environmental protection, worker safety, or community consent. One of the most emblematic cases is Taboshar in northern Tajikistan, where uranium was mined and milled intensively from the 1940s through the 1960s. When operations ceased, tailings and radioactive waste were left largely untreated. Decades later, uncovered tailings piles remain exposed to erosion, flooding, and wind dispersion, posing persistent health and environmental risks to local populations.

Similar legacies exist in Mailuu-Suu in southern Kyrgyzstan, often cited as one of the world’s most hazardous uranium tailings sites due to its location in a landslide-prone area above major river systems.

These sites illustrate a critical lesson: while uranium endowment can be an economic asset, its development without robust governance can impose long-term social and fiscal liabilities that dwarf short-term gains (See Table 1 below.) This historical memory continues to shape public perceptions of uranium projects across Central Asia, making legitimacy, transparency, and safety as important as geology.

Uranium as a New Arena of Great-Power Competition

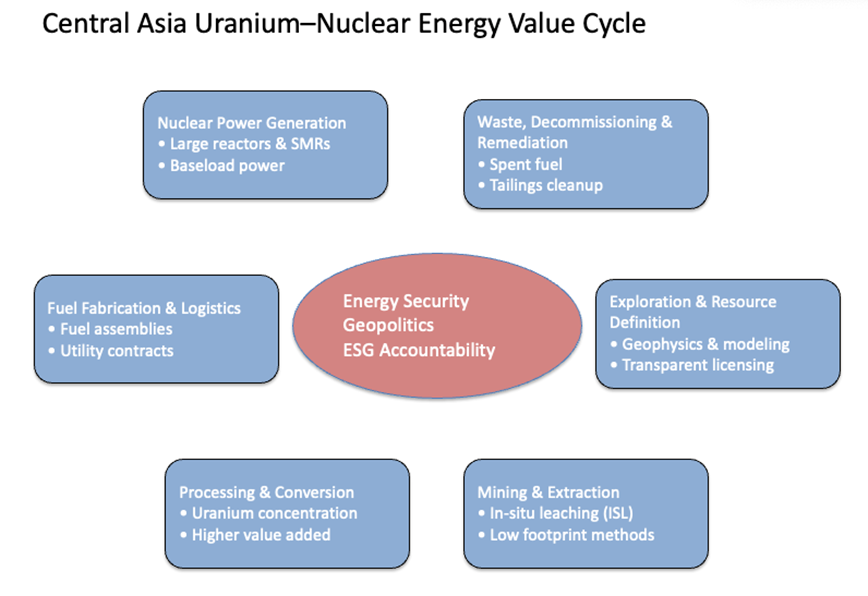

The revival of nuclear energy has quietly but decisively transformed uranium from a relatively technical commodity into a strategic geopolitical asset, and nowhere is this shift more visible than in Central Asia. As global demand for low-carbon baseload power rises and supply chains for nuclear fuel become increasingly politicized, the region has emerged as a focal point of competition among Russia, China, and Western actors, each pursuing distinct strategies across the uranium and nuclear value chain, and each reshaping Central Asia’s development choices in different ways.

Russia Consolidates Influence over Technical Standards and Long-Term System Design in Central Asia

Russia remains the most deeply embedded and operationally dominant external player. Through Rosatom, Moscow offers Central Asian governments a vertically integrated nuclear model that spans uranium mining partnerships, fuel fabrication, reactor construction, long-term operation and maintenance, and spent fuel management.

This model has already moved from theory to implementation. In Kazakhstan, Rosatom has been selected to lead the consortium building the country’s first nuclear power plant, following a national referendum approving nuclear energy. The project, based on VVER-1200 Generation III+ reactors, is expected to anchor Kazakhstan’s future baseload electricity supply as coal capacity declines and power demand rises. At the same time, Kazakhstan is planning a second nuclear plant, creating space for vendor competition, but Rosatom’s first-mover advantage gives Russia significant influence over technical standards, fuel contracts, and long-term system design.

In Uzbekistan, Russia’s role is even more pronounced. Rosatom has signed agreements to construct a small modular reactor plant in the Jizzakh region using the RITM-200N design, with discussions also covering the possibility of larger reactors in the future. If fully implemented, these projects would substantially increase Uzbekistan’s domestic demand for uranium and lock the country into Russian nuclear technology, fuel supply arrangements, and servicing contracts for decades. For governments facing acute energy shortages, this “turnkey” approach is attractive: it offers speed, sovereign-backed financing, and a clear pathway to new generating capacity.

Yet the same integration that makes the Russian model efficient also creates structural dependence. Long-term fuel supply agreements, proprietary technologies, and reliance on Russian operators reduce future flexibility, while sanctions risks, already evident in uranium joint ventures involving Russian equity, can complicate access to Western finance, insurance, and export markets. There is also a governance dimension: if nuclear projects are negotiated through opaque bilateral channels, competition can be crowded out and environmental and social safeguards weakened, echoing some of the negative legacies of Soviet-era nuclear development.

China Prioritizes the Strategic Acquisition of Upstream Uranium Resources

China’s strategy in Central Asia is more incremental but no less strategic. Rather than prioritizing large-scale reactor exports in the short term, Beijing has focused on securing upstream uranium resources and long-term offtake to supply its rapidly expanding domestic nuclear fleet, now the largest under construction globally. Chinese state-owned enterprises such as China National Nuclear Corporation and China General Nuclear Power Group have acquired equity stakes in several Kazakh uranium joint ventures and signed long-term supply agreements, positioning China as one of the most important downstream buyers of Central Asian uranium. More recently, Kazakhstan has indicated that Chinese firms will lead a consortium for a second nuclear power plant, creating a parallel nuclear platform alongside the Rosatom-led project.

Beyond Kazakhstan, Chinese geological teams have revisited Soviet-era data in Tajikistan, reassessing uranium potential in a country marked by significant legacy contamination and unresolved tailings issues. While no large-scale commercial mining projects have yet been publicly confirmed, this upstream engagement reflects China’s long-term approach: patient capital, early positioning, and integration with broader infrastructure investments in transport, power transmission, and processing facilities. For Central Asian governments, Chinese participation offers diversification and access to financing that is often less conditional than Western alternatives. At the same time, it raises concerns about transparency, environmental oversight, and debt exposure, particularly if upstream extraction advances faster than regulatory capacity and community engagement frameworks.

Western Strategic Engagement Focuses on Diversifying Global Supply Chains and Embedding High Governance Standards

The United States and its allies pursue a different, more fragmented strategy. Rather than seeking dominance through mining or turnkey nuclear packages, Western engagement has focused on diversifying global nuclear fuel supply chains away from Russia, promoting advanced reactor technologies, and embedding high environmental, social, and governance standards. Direct U.S. equity participation in uranium mining in Central Asia has been limited, reflecting stricter compliance requirements and political caution. Nevertheless, Western and allied companies are increasingly visible across downstream and enabling segments of the value chain.

In uranium mining and processing, French Orano has emerged as a key Western-standard player through joint ventures with Uzbekistan’s state uranium producer, while Japan’s ITOCHU has taken minority stakes, bringing diversified governance and access to Asian fuel markets. These projects explicitly emphasize international environmental and safety standards, offering a contrast to more state-centric models and demonstrating that high-compliance uranium development is feasible in the region. In the reactor space, Western and allied vendors such as EDF, KHNP, and U.S.-linked SMR developers like NuScale Power and GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy have all expressed interest or participated in technology shortlists and discussions in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, even where they have not ultimately secured contracts.

Western engagement is also expanding in less visible but strategically important areas: nuclear safety regulation, workforce training, fuel services, and the remediation of legacy uranium sites—an area where Central Asia’s Soviet inheritance remains particularly acute. This approach is slower and more conditional, but it offers reputational benefits, access to OECD capital markets, and lower long-term environmental and social risk.

Weak Governance rather than Geopolitical Competition as the Primary Risk to Central Asian Strategic Interests

For Central Asian states, the resulting competition is not inherently destabilizing; in fact, it creates leverage. By sequencing projects carefully, separating upstream mining decisions from downstream nuclear build-outs, and maintaining genuine competition among Russian, Chinese, and Western partners, governments can avoid exclusive dependence and negotiate better terms for technology transfer, localization, environmental protection, and revenue management. The danger lies not in competition itself, but in weak governance. Without transparent procurement, independent regulation, and enforceable environmental and social safeguards, geopolitical rivalry risks devolving into fragmented bilateral deals that lock countries into narrow technological pathways and reproduce the long-term liabilities of the past. Managed strategically, however, Central Asia’s uranium endowment can become not merely a prize contested by external powers, but a foundation for greater energy security, industrial upgrading, and strategic autonomy.

Global Context: Central Asia in the World Uranium Balance

Globally, uranium demand is rising again after a decade-long post-Fukushima slowdown. As of the mid-2020s, nuclear power provides roughly 10 percent of global electricity, but it accounts for nearly one-quarter of low-carbon electricity generation. More than 60 reactors are under construction worldwide, with over 100 additional units planned or proposed, primarily in Asia and the Middle East. This trajectory implies a structural tightening of the uranium market over the next decade.

In this context, Central Asia’s role is outsized. Kazakhstan’s low-cost in-situ leaching (ISL) operations place it at the bottom of the global cost curve, giving it price-setting power during periods of supply tightness. Uzbekistan’s strategy to expand exploration and improve recovery rates could further consolidate the region’s importance. By contrast, uranium resources in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are modest in global terms, but their geopolitical and environmental significance is high due to legacy contamination and their potential re-entry into the market under new regulatory regimes. The key point is that Central Asia is not a marginal supplier. It is a systemically important player in the global nuclear fuel cycle, and shifts in its production, governance, or export orientation have global repercussions.

Investment Potential Across the Full Uranium Value Chain

Uranium development should not be viewed narrowly as mining. Global best practice shows that the greatest economic and technological benefits arise when countries integrate across the value chain:

International experience—from Canada to Australia—demonstrates that strong domestic regulation combined with openness to high-standard foreign investors can turn uranium from a narrow extractive sector into a catalyst for industrial upgrading, research capacity, and skilled employment.

Social and Environmental Risks: Lessons from the Past

The Soviet legacy looms large. Sites like Taboshar and Mailuu-Suu are reminders that uranium mismanagement creates intergenerational harm. Uncovered tailings, contaminated water, and poorly documented waste repositories continue to pose risks decades after mine closure. These legacies also undermine trust in new projects, even when modern technologies are proposed.

New uranium development, if poorly governed, risks repeating these mistakes: land displacement, water contamination, inadequate tailings management, and insufficient community consultation. Academic research underscores that environmental threats and public distrust remain among the key constraints on uranium projects in Central Asia, alongside geopolitical rivalry and institutional weakness

Responsible Investment and ESG in the Uranium Industry

Responsible investment is not a slogan in uranium, it is a precondition for legitimacy. ESG in the uranium context means:

- Environmental: strict radiation safety standards, secure tailings storage, water protection, lifecycle planning from exploration to closure, and funded remediation plans.

- Social: informed community consent, transparent benefit-sharing, health monitoring, and protection of vulnerable groups.

- Governance: independent regulators, transparent licensing, competitive procurement, and alignment with international conventions on nuclear safety and non-proliferation.

Countries that fail to enforce these standards may attract capital in the short term, but they incur long-term fiscal and political costs through cleanup liabilities, social unrest, and reputational damage.

Governance and Regulatory Gaps in Central Asia

Despite visible progress in reforming extractive-sector legislation over the past decade, uranium governance frameworks across much of Central Asia remain fragmented, unevenly enforced, and structurally weak. This gap between formal rules and actual practice is particularly consequential in the uranium sector, where environmental, health, and security risks are inherently higher than in conventional mining and where failures generate long-term, often irreversible liabilities.

The Erosion of Institutional Independence and Technical Oversight Capacity

A central challenge is the limited independence and capacity of regulatory institutions. In several Central Asian countries, nuclear and radiation oversight functions are dispersed across ministries with overlapping mandates, weak coordination, and insufficient insulation from political and commercial pressure. Regulators are frequently under-resourced, lack modern monitoring equipment, and depend on data self-reported by operators. This undermines credible enforcement of radiation safety standards, groundwater protection, tailings management, and mine-closure obligations—precisely the areas where uranium mining poses the greatest risks.

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) systems formally exist but are often procedural rather than substantive. EIAs tend to focus on initial project approval rather than lifecycle risks, with limited attention to cumulative impacts, long-term tailings stability, or post-closure liabilities. Public consultations, where conducted, are frequently narrow in scope and poorly trusted, reflecting both weak disclosure practices and the legacy of Soviet-era secrecy surrounding nuclear activities. As a result, local communities often perceive uranium projects as imposed rather than negotiated, increasing the likelihood of resistance, litigation, or political backlash once operations begin.

Licensing Ambiguity and the Strategic Exclusion of High Compliance International Capital

Another structural weakness lies in licensing and competition frameworks. Uranium projects are commonly awarded through negotiated arrangements or government-to-government deals rather than transparent, competitive tenders. While this can accelerate project launch—particularly for nuclear power plants bundled with financing—it also reduces price discovery, limits investor diversity, and entrenches incumbent or geopolitically favored partners. Over time, this dynamic discourages high-compliance international firms that require predictable, rule-based processes, while favoring investors more tolerant of regulatory ambiguity and political risk.

Revenue management and liability allocation further illustrate governance gaps. In several cases, mine-closure responsibilities, tailings rehabilitation, and long-term environmental monitoring are insufficiently costed or weakly secured through financial guarantees. This raises the risk that cleanup costs will eventually be socialized—borne by governments and communities rather than operators—repeating the Soviet legacy evident in sites such as Taboshar or Mailuu-Suu. From an investor perspective, this uncertainty also increases sovereign contingent liabilities, complicating fiscal planning and debt sustainability.

Establishing Credible Governance through Independent Oversight and Enforceable Financial Guarantees

Addressing these gaps requires more than incremental legal amendments. A credible uranium governance framework must rest on independent nuclear and radiation regulators with clear mandates, professional staffing, and enforcement authority, insulated from both political cycles and commercial interests. Mine-closure and remediation obligations need to be clearly defined ex ante, fully costed, and backed by enforceable financial instruments. Transparency in licensing, contracting, and revenue flows is essential—not only to reduce corruption risks, but to signal seriousness to institutional investors bound by ESG and compliance requirements.

Equally important is regional cooperation. Uranium risks in Central Asia are rarely contained within national borders: groundwater systems, river basins, seismic zones, and even radioactive dust transport are transboundary by nature. Fragmented national approaches increase collective vulnerability. Harmonizing safety standards, sharing monitoring data, and coordinating emergency response mechanisms would significantly strengthen regional resilience while lowering costs for individual states.

Aligning national uranium governance frameworks with international norms and best practice—including IAEA safety standards, international mine-closure principles, and modern ESG disclosure requirements—would have a double dividend. It would materially reduce environmental and social risks for local populations, while simultaneously expanding the pool of credible, long-term investors willing to engage across the uranium value chain. In a sector where capital is mobile but reputational risk is high, governance quality is not a constraint on development; it is a precondition for sustainable participation in the global nuclear economy.

Table 1: Key Governance and Regulatory Gaps in Central Asia’s Uranium Sector

| Governance Area | Current Gap in Central Asia | Why It Matters (Risks) | Implications for Investment & Geopolitics |

| Regulatory Independence | Nuclear, radiation, and mining oversight bodies often lack institutional independence and clear separation from line ministries or SOEs | Weak enforcement of safety, radiation, and environmental standards; regulatory capture | Discourages high-compliance investors; favors state-linked or geopolitically backed firms |

| Technical & Monitoring Capacity | Regulators under-resourced; limited modern equipment for radiation, groundwater, and tailings monitoring | Inability to detect leaks, contamination, or non-compliance early | Raises long-term environmental liabilities; increases sovereign risk |

| Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) | EIAs often formalistic, front-loaded, and project-specific; weak lifecycle and cumulative impact analysis | Long-term risks (tailings stability, water contamination) underpriced or ignored | Heightens risk of future social backlash, litigation, or donor withdrawal |

| Public Participation & Transparency | Limited access to project data; consultations narrow, late-stage, or poorly trusted | Low social license; heightened community resistance | Political risk premium increases; projects vulnerable to protests or reversals |

| Licensing & Tendering | Negotiated deals and G2G agreements dominate over competitive tenders | Reduced price discovery; weak competition | Locks countries into single partners (often Russia or China); limits leverage |

| Mine Closure & Remediation Rules | Closure obligations often vague or weakly enforced; insufficient financial guarantees | Cleanup costs shift to governments and communities | Recreates Soviet-era legacy sites (e.g. tailings); deters ESG-driven capital |

| Tailings & Waste Management | Inconsistent standards; legacy tailings insufficiently secured or remediated | Persistent radiation and transboundary pollution risks | International reputational damage; donor and insurer reluctance |

| Revenue Transparency | Limited disclosure of contracts, fiscal terms, and off-budget liabilities | Corruption risk; elite capture | Undermines public trust; complicates IMF/WB fiscal assessments |

| Security & Safeguards | Uneven alignment with international nuclear security and safeguards norms | Proliferation and security concerns | Raises geopolitical scrutiny; limits cooperation with Western partners |

| Regional Coordination | Weak cross-border cooperation on water, seismic, and contamination risks | Transboundary accidents unmanaged | Regional instability; higher collective vulnerability |

| ESG Alignment | ESG applied inconsistently; often treated as compliance “add-on” | Environmental and social risks mispriced | Only geopolitically motivated investors proceed; high-quality capital stays out |