Afghanistan’s Break with Pakistan Opens Door for India

Four years after India shut its Kabul embassy following the Taliban’s return, bilateral trade has nearly rebounded to pre-2021 levels—even as Afghanistan’s trade through Pakistan collapses. This reversal highlights Pakistan’s waning leverage and India’s quiet re-emergence as a key economic and diplomatic player, a trend that increasingly links Afghanistan’s revival to India’s wider westward strategic turn, with Kabul serving as New Delhi’s gateway to Central Asia.

Our research fellows, Vladimir Paddack and Eldaniz Gusseinov, published a joint analytical article on The National Interest‘s website. They argue that Afghanistan’s trade and diplomacy are shifting in unexpected ways that reflect broader regional realignments.

Afghan-Indian Trade Revival

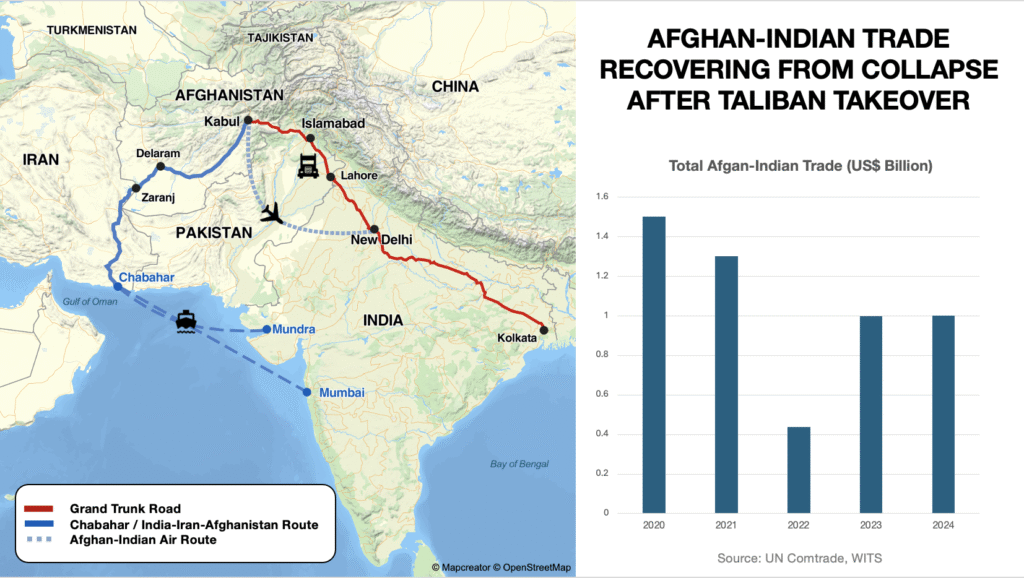

Before 2021, India–Afghanistan trade reached $1.33 billion, with India exporting $826 million and importing $509 million in Afghan goods. After the Taliban takeover, India’s exports plunged to $437 million in 2022–23. But by FY 2023–24, trade surged back to $997.7 million, driven by Afghan exports of dried fruits, saffron, nuts, and apples — now duty-free in India. Afghan exports hit a record $642 million, giving India a trade deficit with Kabul for the first time.

Between April 2024 and March 2025 alone, trade reached $1 billion, signalling full recovery by year’s end. Both sides are exploring Iran’s Chabahar Port, developed by India, to bypass Pakistan. India also plans to reopen its Kabul embassy and resume direct flights, reflecting what Dr. Shanthie Mariet D’Souza calls a shift from “cautious engagement” to reconnecting and rebuilding ties.

The graph shows that Afghan-Indian trade, which sharply declined after the Taliban takeover in 2021, has gradually recovered since 2022, stabilizing at around $1 billion in 2023–2024.

Breakdown With Pakistan

While ties with India deepen, Afghanistan’s trade with Pakistan — once its economic lifeline — is collapsing. Transit trade through Pakistan dropped from $7 billion in 2022 to $2.9 billion in 2024, an almost 60 percent fall. Between November 2023–24 alone, it plunged 84 percent to $1.2 billion, due to Islamabad’s anti-smuggling drives, tighter customs, and frequent border closures amid rising border clashes.

Though direct bilateral trade rose modestly, Pakistan’s role as a transit hub has eroded. The decline mirrors political tensions: Islamabad accuses Kabul of harbouring TTP militants, while Kabul denies it. On 9 October, Pakistan launched an unprecedented airstrike on Kabul, coinciding with Taliban Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi’s visit to New Delhi — an unmistakable signal of shifting loyalties.

A New Regional Balance

India’s outreach to the Taliban reflects strategic pragmatism amid Russia’s recognition of the regime, China’s growing role, and Pakistan–Afghanistan tensions. New Delhi aims to regain influence lost in 2021 and prevent Afghanistan from tilting fully toward Beijing or Islamabad. For the Taliban, India offers investment and a counterweight to Pakistan. Afghanistan’s potential in minerals, horticulture, and agriculture, as Dr. D’Souza notes, presents lucrative opportunities for Indian firms.

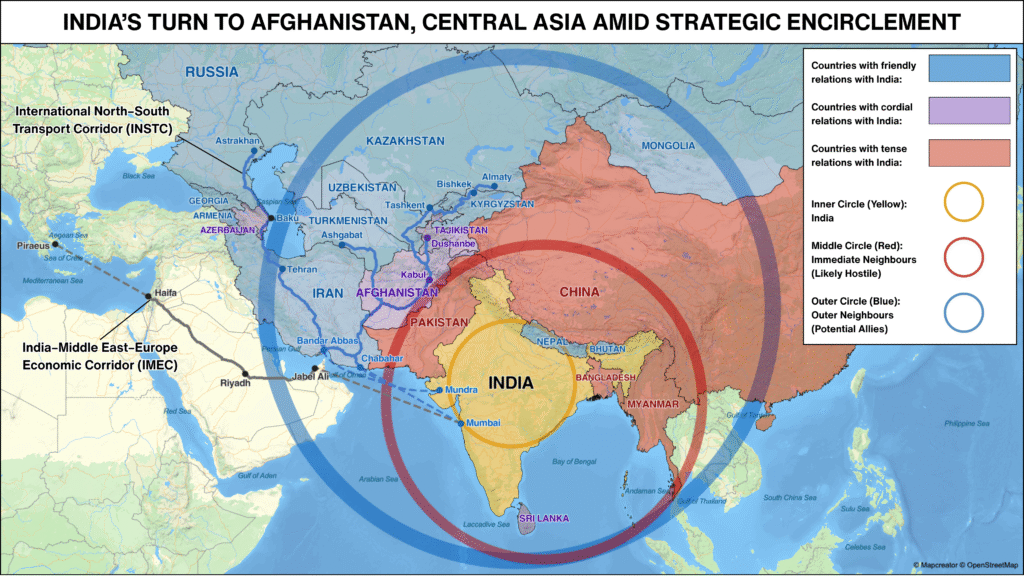

Both sides also share an interest in regional connectivity — “Afghanistan is crucial as a land bridge for India in terms of connectivity to Central Asia,” she emphasises. India’s growing investment in the Chabahar Port and overland corridors through Afghanistan underscores a broader realignment — one in which India is turning decisively westward to find strategic depth beyond encirclement.

India Turns Westward to Escape Encirclement

India’s renewed engagement with Afghanistan is also driven by an urgent reality – encirclement by China’s expanding influence. Pro-Chinese governments have taken hold in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and until September, Nepal, eroding India’s traditional sway, while Pakistan remains firmly aligned with China. According to Vlad Paddack, New Delhi is recalibrating its approach, looking westward to seek out new partnerships.

This logic echoes the ancient Rajamandala theory of Indian strategist Chanakya, which holds that a neighbour’s neighbour is a natural ally against immediate adversaries. As its neighbourhood tilts toward Beijing, India is seeking partnerships with Afghanistan, Iran and Central Asia to form concentric alliances that balance Chinese and Pakistani influence and reassert India’s role in the emerging Eurasian order.

The map illustrates India’s growing outreach to Afghanistan and Central Asia as part of its strategy to counter regional isolation, seeking allies beyond its immediate neighborhood amid tense relations with China and Pakistan.

Iran’s Chabahar Anchor

Iran’s Chabahar port remains the cornerstone of India’s westward strategy — a sanctions-exempt, India-run port that anchors regional trade while bypassing Pakistan. Under a 10-year deal signed in May 2024, and integrated with the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), Chabahar has the potential to handle 8.5 million tons of cargo, becoming a vital artery for Indian exports of pharmaceuticals, machinery and vehicles to Eurasia.

The port also serves as Afghanistan and Central Asia’s access point to the Arabian Sea. India is investing $120m in upgrades and offering a $250m credit line to expand capacity, while Taliban officials declared a $35m investment in the port. Despite competition from China’s Gwadar Port, Chabahar endures as India’s most reliable maritime lifeline and a crucial pillar of its westward realignment.

Afghanistan as India’s Gateway to Central Asia

Afghanistan lies at the heart of India’s westward strategy. Through overland corridors via Herat and Turkmenistan, India can bypass Pakistan and gain direct access to Central Asia. The region’s transport map now revolves around two rival routes: the eastern Uzbekistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan (UAP) railway tied to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and a western Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Afghanistan (KTA) route favoured by India – slower but strategically safer.

India’s challenge is that the UAP could cut transit time from 35 days to 5, boosting Pakistan’s growing export base. India, though leading with $880m in exports to Central Asia compared to Pakistan’s $402m, risks losing ground if eastern routes dominate. For India, KTA is both a hedge and a necessity, ensuring reliable connectivity to Central Asia free from Pakistani or Chinese control.

Conclusion

Ultimately, India’s engagement with Afghanistan – as a trading partner and transit ally – represents more than a tactical adjustment. It signals a larger strategic repositioning: encircled by China’s influence, India is turning westward through Afghanistan and Iran, reviving the logic of Chanakya’s “circle of states” to craft concentric partnerships that balance Chinese and Pakistani influence and reassert India’s role in the evolving Eurasian order.