Central Asia’s Yuan Adoption Creates New Challenges for Business

The yuan is not replacing the dollar in Central Asia — but it is becoming structurally embedded in the region’s financial system.

In February 2025, Nightingale analysts Sobir Kurbanov and Vlad Paddack published their analysis “Between Dollar and Dragon: Geopolitics of Rising Yuan” in The Astana Times, examining how the Chinese renminbi is quietly gaining ground in Central Asian financial systems. The piece traced the interplay of sanctions pressure, tightening dollar liquidity, and China’s expanding trade and lending networks that are gradually reshaping how the region settles financial affairs.

Central Asia is becoming not merely a transit corridor for China, but an important partner in China’s financial continental architecture.

The article mapped the terrain. Here, we want to go further — offering our readers scenario-based analysis and practical recommendations for businesses operating in or entering Central Asia, because what is unfolding is a financial dimension of a much deeper structural integration between China and the region, one that Nightingale has been tracking across transport, security, and economic domains throughout 2026.

Key Takeaways for Businesss

1. The yuan is gaining ground through trade, not politics. Yuan adoption in Central Asia is driven by commercial logic — importers settle in yuan because it reduces costs with Chinese suppliers, not because governments are pivoting toward Beijing. This means the trend will deepen as trade volumes grow, regardless of official policy.

2. Financial integration follows infrastructure. As the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway becomes operational and Khorgos processes more freight, demand for yuan-denominated settlement will expand accordingly. Companies should watch infrastructure milestones as leading indicators for currency shifts.

3. The competitive environment depends on Western action. Whether Central Asia preserves multi-currency flexibility or drifts toward yuan dependence hinges on whether Western financial institutions move beyond memorandums to concrete products — trade finance, clearing services, and lending that can compete with what Chinese banks already offer on the ground.

4. Multi-currency capability is no longer optional. Across all three scenarios, currency diversification increases. Companies that build treasury flexibility now — the ability to hold, settle, and hedge across dollars, yuan, and potentially regional mechanisms — will outperform those forced to adapt reactively.

Financial Integration Follows Physical Integration

The yuan’s expanding role in Central Asia cannot be understood in isolation from the infrastructure and security architecture China is building across the region. Over the past year, Nightingale’s analysis has documented how Beijing is constructing what amounts to a continental system of connectivity — the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway finally breaking ground after 25 years of negotiations, a third rail link with Kazakhstan under development, road modernization in Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan, and the expansion of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor into Afghanistan through trilateral diplomacy.

This physical integration has accelerated precisely because China’s alternative routes are under stress. The closure of the Poland-Belarus crossing at Małaszewicze disrupted the primary rail corridor to Europe. Escalation between India and Pakistan threatened the CPEC corridor and port access at Gwadar and Karachi. Political crisis in Iran undermined the viability of the Chabahar transit route.

The American TRIPP initiative introduced competitor infrastructure in the South Caucasus. Each disruption has reinforced Beijing’s conclusion that Central Asian stability is inseparable from Chinese stability — a principle now codified in the Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighborliness, Friendship, and Cooperation signed in Astana in June 2025.

Where physical infrastructure flows, financial infrastructure follows. As trade volumes through Xinjiang’s border crossings grow — Central Asia now accounts for roughly 55 percent of Xinjiang’s total foreign trade — so does the practical demand for yuan-denominated settlement.

Over 300,000 vehicles were exported through Khorgos alone in the first ten months of 2025. Importers across the region increasingly invoice in yuan not because of geopolitical alignment but because it reduces transaction costs when dealing with Chinese suppliers.

Commercial banks in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have responded by offering yuan deposits, trade finance, and clearing services. This is financial integration driven by commercial gravity.

The implication for business is straightforward: the yuan’s role in Central Asia will continue to expand not at the pace of policy announcements but at the pace of infrastructure completion and trade growth.

As the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway becomes operational, as Khorgos processes more freight, as Chinese manufacturing relocates to Uzbekistan’s special economic zones, the financial plumbing will adapt accordingly.

Companies operating in the region need to plan for a currency environment that is structurally more diversified than it was five years ago.

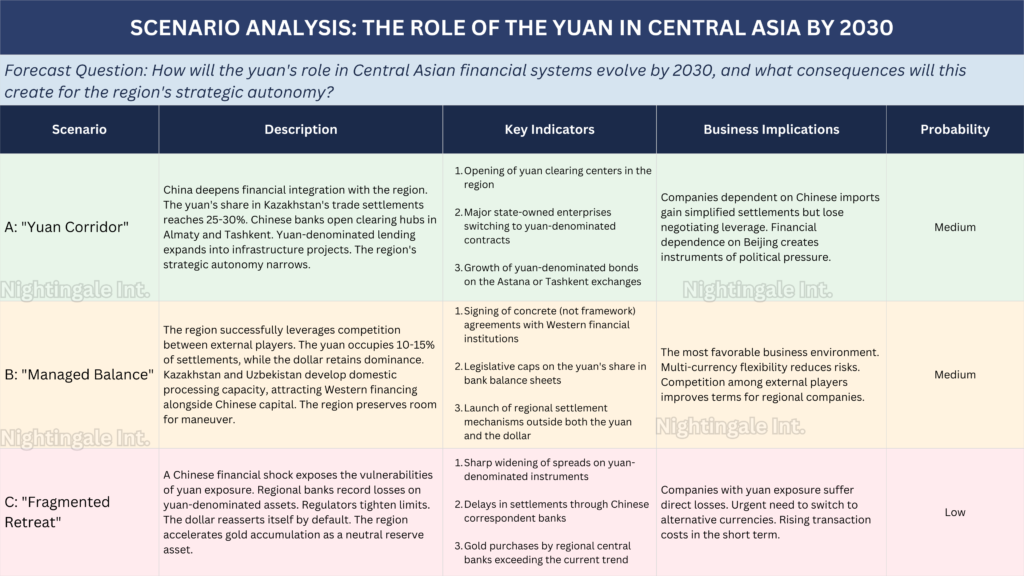

Three Scenarios for the Yuan’s Role in Central Asia by 2030

Building on our analysis published in The Astana Times and Nightingale’s ongoing tracking of China’s deepening structural integration with Central Asia, we have developed three strategic scenarios for the yuan’s role in the region’s financial systems through 2030. The following table compares these pathways, outlining specific indicators and long-term consequences to help businesses visualize the shift from dollar dominance toward a more fragmented currency environment.

Scenario A — “Yuan Corridor” (Deep Financial Integration)

China deepens financial integration with Central Asia. The yuan’s share in Kazakhstan’s trade settlements reaches 25–30%. Chinese banks establish clearing hubs in Almaty and Tashkent. Yuan-denominated lending expands into infrastructure projects. The region’s strategic autonomy narrows.

Indicators:

- Opening of yuan clearing centers in the region

- Major state-owned enterprises switching to yuan-denominated contracts

- Growth of yuan-denominated bonds on the Astana or Tashkent exchanges

Consequences:

- Companies dependent on Chinese imports gain simplified settlements but lose negotiating leverage

- Financial dependence on Beijing creates instruments of political pressure

- Western financial institutions lose market share in regional trade finance

- Reduced flexibility for governments in foreign policy decision-making

Probability: Medium — requires sustained Chinese policy push and insufficient Western financial counter-offers

Scenario B — “Managed Balance” (Competitive Equilibrium)

The region successfully leverages competition between external players. The yuan occupies 10–15% of settlements while the dollar retains dominance. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan develop domestic processing capacity, attracting Western financing alongside Chinese capital. Regional clearing mechanisms emerge outside both yuan and dollar systems.

Indicators:

- Signing of concrete (not framework) agreements with Western financial institutions

- Legislative caps on the yuan’s share in bank balance sheets

- Launch of regional settlement mechanisms outside both the yuan and the dollar

Consequences:

- Most favorable environment for business: multi-currency flexibility reduces risk

- Competition among external actors improves terms for regional companies

- Governments preserve strategic room for maneuver

- Real substance to Central Asia’s multi-vector economic policy

Probability: Medium — contingent on whether Western financial institutions move from memorandums to concrete commitments

Scenario C — “Fragmented Retreat” (Financial Shock)

A Chinese financial shock exposes the vulnerabilities of yuan exposure. Regional banks record losses on yuan-denominated assets. Regulators tighten limits. The dollar reasserts itself by default. Central banks accelerate gold accumulation as a neutral reserve asset.

Indicators:

- Sharp widening of spreads on yuan-denominated instruments

- Delays in settlements through Chinese correspondent banks

- Gold purchases by regional central banks exceeding the current trend

Consequences:

- Companies with yuan exposure suffer direct losses

- Urgent need to switch to alternative currencies with rising transaction costs

- Renewed dependence on dollar infrastructure without improved Western engagement

- Accelerated shift toward gold as a neutral reserve hedge

Probability: Lower but not negligible — given structural risks embedded in China’s managed exchange rate and the limited convertibility of the renminbi

Recommendations for Businesses

1. Build multi-currency treasury capability now

The direction of travel is toward greater currency diversification regardless of which scenario dominates. Companies operating in Central Asia should develop the ability to hold, settle, and hedge in multiple currencies — including the yuan — rather than waiting for a single scenario to materialize. The cost of adaptation rises the longer it is deferred. Firms that build this flexibility early will have a structural advantage over those forced to react under pressure.

2. Monitor leading indicators for each scenario

Each scenario produces distinct early warning signals. Track the opening of yuan clearing centers and the growth of yuan-denominated bonds (Scenario A), the signing of concrete Western financial agreements and legislative caps on yuan exposure (Scenario B), or widening spreads on yuan instruments and settlement delays through Chinese correspondent banks (Scenario C). These indicators reveal which trajectory the region is following before the consequences reach your balance sheet.

3. Understand that financial integration follows physical integration

The yuan’s rise is not an isolated monetary phenomenon. It is one dimension of a comprehensive Chinese strategy to bind Central Asia into its continental architecture — through railways, border infrastructure, security cooperation, and manufacturing relocation. The companies best positioned to navigate the next five years will be those that read the financial environment through this wider lens. The business landscape of 2030 will be shaped by decisions being made today in railway construction and border digitization as much as by central bank reserve allocations.

At Nightingale Int., we support companies operating across Eurasia in understanding geopolitical risks before they turn into operational threats. We translate political instability, sanctions dynamics, and security shifts into clear, actionable intelligence for business decision-makers. Companies can contact us directly via our form: https://nightingale-int.com/contact-us/ .