EU–India Free Trade Deal at Risk from Middle East Instability

Business should treat the EU–India Free Trade Agreement (FTA) as a revenue opportunity arriving into a logistics environment defined by longer transit times and sanctions uncertainty. Because tariff savings only materialize if goods move reliably, Middle East instability can quietly erode margins and delivery performance in the first years of the deal.

The agreement’s ambition is large: public reporting describes tariff reductions covering the vast majority of trade by value and EU expectations of multi-billion euro annual duty savings and a major export expansion over the decade, precisely the kind of growth that makes logistics friction a first-order business risk.

Five Key Takeaways for Business

- The FTA magnifies exposure to shipping reliability, not just tariff schedules: duty cuts matter less if lead times swing and inventory buffers must expand.

- Red Sea/Bab el-Mandeb risk is now a structural planning variable: diversions around the Cape of Good Hope typically add ~10 days or more to Asia–Europe voyages and tie up working capital.

- Freight and insurance volatility will compress “headline” FTA gains, especially for low-margin, time-sensitive goods (apparel, consumer electronics, automotive components).

- Diversification routes are politically contingent: Iran-linked options depend on sanctions/waivers, while IMEC-style land–sea bridges depend on stable Eastern Mediterranean politics.

- The ratification window is a strategic runway: firms can redesign sourcing and logistics before the FTA’s tariff changes fully bite.

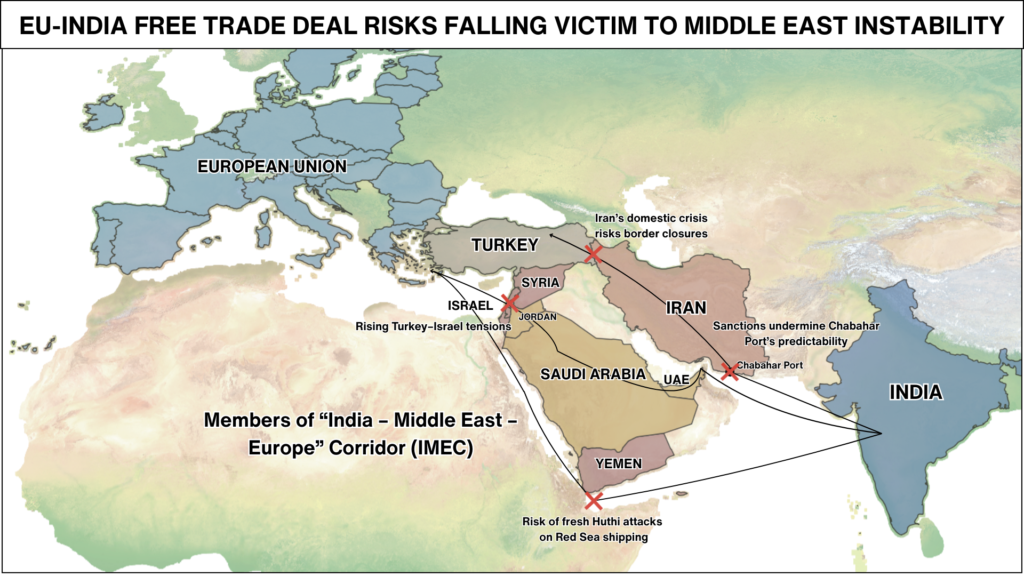

Current Instability Is Disrupting India–EU Trade Routes

For most India–EU cargo, the shortest maritime artery runs via the Arabian Sea–Bab el-Mandeb–Red Sea–Suez chain. The IMF notes that Red Sea attacks reduced traffic through Suez and pushed carriers to divert around the Cape of Good Hope, increasing delivery times by 10 days or more and hurting firms with tight inventories. The OECD/ITF similarly details how rerouting raises operating costs for container shipping and feeds through to supply chains.

The extension of the EU’s defensive maritime mission (Operation ASPIDES) until the end of February 2026 is an indirect signal that the current status quo is likely to be preserved.

Operationally, that means:

- longer and less predictable lead times;

- higher logistics and insurance costs that eat into tariff-driven margin upside;

- greater contract risk (late-delivery penalties, force majeure disputes) as routing becomes dynamic.

The Middle East also complicates two often-cited “relief valves” for India–EU trade.

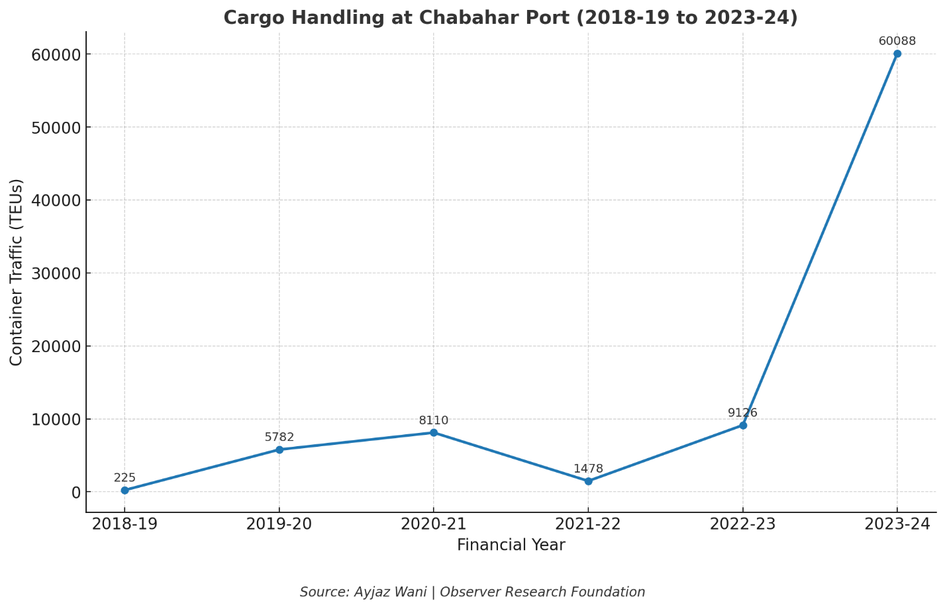

First, Iran-linked corridors (INSTC/Chabahar) can diversify away from Suez, but their commercial scaling is conditioned on U.S. sanctions policy. Reuters reported Washington granted India a six-month exemption for Chabahar, and India’s foreign ministry has publicly referenced a conditional waiver valid until 26 April 2026, which is useful for continuity, but not a stable basis for long-horizon supply chain commitments.

Moreover, the European Union has added the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) to its list of terrorist organizations, which means that the EU will oppose transit through Iran that could indirectly finance IRGC activities.

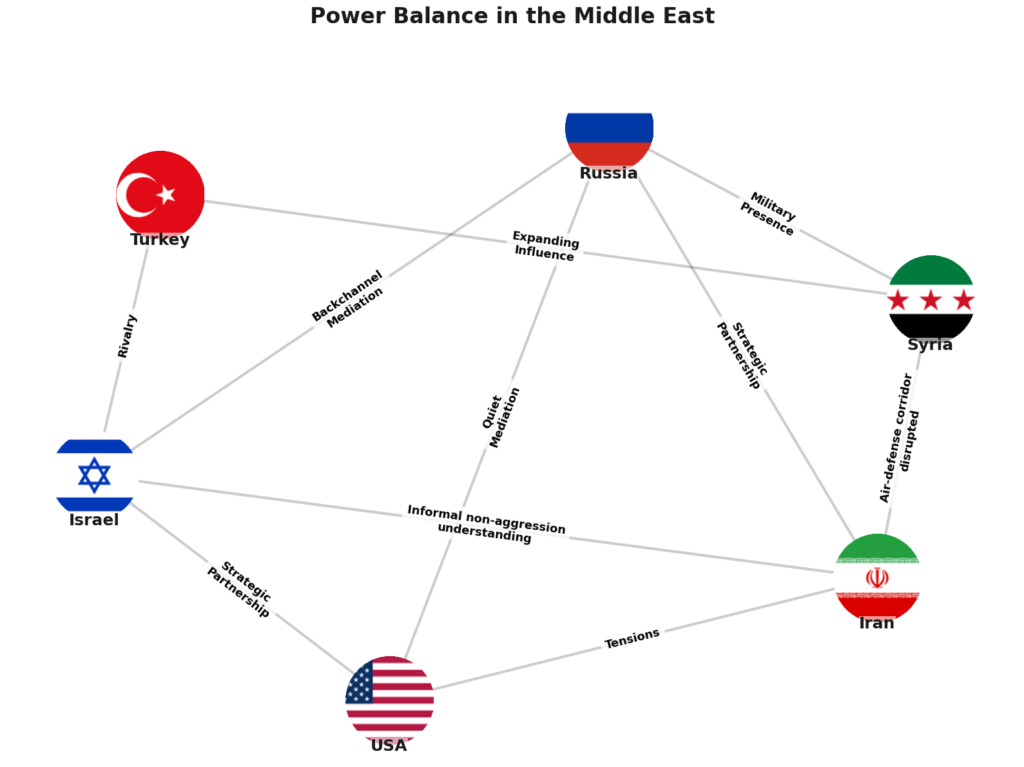

Second, IMEC has regained political emphasis in EU–India statements, but it relies on a seamless Gulf–Levant–Mediterranean interface; conflict risk around Israel-linked nodes makes it a medium- to long-term bet rather than immediate capacity. It is important to note that Turkey is seeking to join a defense pact with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Following the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, the role of the Middle East in Turkey’s foreign policy has significantly increased. This shift implies a relative decline in Iran’s role as Israel’s primary regional adversary, with Turkey potentially emerging as the new strategic challenger.

Particularly notable is the strengthening of cooperation between Israel and Greece. This directly affects Turkey, which has longstanding disputes with Greece.

The Greek–Israeli rapprochement is most plausibly mediated through the Mediterranean space and the Port of Haifa, located just 60–100 km from the Israeli–Syrian border. This proximity increases the geopolitical weight of the axis Greece-Israel and is likely to trigger a sharper competitive response from Turkey toward Israel.

Overall, instability along Israel’s borders casts doubt on the feasibility of fully implementing IMEC, despite the growing political momentum around the project following the signing of the India–EU Free Trade Agreement.

Time Is on the EU–India Side: A Strategic Implementation Window

The FTA was concluded at the 16th EU–India summit on 27 January 2026, but it still requires legal finalization and approvals before it can enter into force. Public reporting on the agreement highlights that ratification steps remain and that implementation is expected later rather than immediately. This matters: the corridor shocks are happening now, while the tariff cuts will phase in over time, giving firms a window to adapt their operating model.

That runway is valuable because it allows companies to:

- model all-in landed cost under multiple routing assumptions (Suez windows vs. sustained Cape diversion and IMEC);

- adjust supplier footprints and rules-of-origin strategies without locking into single-route dependence;

- renegotiate commercial protections (freight indexation, flexible incoterms, clearer force majeure triggers).

Bottom line: Middle East instability threatens the efficiency and predictability gains that should accompany the FTA, but it is more likely to tax early implementation economics than to derail the political deal itself.

Three Recommendations for Business

- Run a 2026 corridor stress test. Build scenarios for (a) prolonged Cape diversion, (b) intermittent Red Sea “windows,” and (c) a tighter Iran sanctions environment after 26 April 2026, then translate them into inventory and service-level plans.

- Contract for resilience, not just price. Revisit incoterms, delivery SLAs, freight pass-through clauses, and force majeure language; diversify carriers/forwarders; and engage insurers early if any ownership/port-call links could elevate war-risk categorization.

- Treat route diversification as a portfolio. Keep at least two viable routing options (maritime + select land/sea alternatives), add buffer warehousing in Europe or Gulf hubs where sensible, and connect compliance alerts to operations so sanctions/security updates translate into routing decisions fast.

At Nightingale Int., we support companies operating across Eurasia in understanding geopolitical risks before they turn into operational threats. We translate political instability, sanctions dynamics, and security shifts into clear, actionable intelligence for business decision-makers. Companies can contact us directly via our form: https://nightingale-int.com/contact-us/ .