Central Asia Is One of the Fastest-Growing Regions Globally

Central Asia is one of the fastest-growing regions globally, but risks are rising in 2026. By the end of 2025, Central Asia had unmistakably returned to the center of global geopolitical and geoeconomic attention. After years of being viewed primarily as a peripheral, landlocked region, the five Central Asian economies (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) found themselves once again embedded in the strategic calculations of major powers and global markets.

This shift was driven by the reconfiguration of Eurasian trade following the Russia–Ukraine war, intensifying competition over critical minerals, and renewed interest in alternative connectivity routes linking East Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

As the year draws to a close and families gather around their tables to say goodbye to the outgoing year and welcome the new one, it is a natural moment to pause and reflect on Central Asia’s main economic highlights, the opportunities now emerging, and the risks that will need careful mitigation as the region enters the next phase of its global re-engagement.

Navigating the Baseline and Beyond

As 2025 closed, the overall picture was one of renewed relevance and cautious optimism. Central Asia had clearly re-entered global markets and strategic thinking, benefiting from its location, resources, and reform momentum. Yet the year also highlighted the limits of a growth model heavily reliant on external shocks, re-exports, and commodity cycles.

Looking ahead to 2026, Central Asia’s outlook is best understood through a set of differentiated but interconnected scenarios rather than a single forecast. Under a baseline scenario, regional growth is expected to moderate slightly but remain robust, likely in the range of 4.5 to 5 %, as reforms continue, connectivity improves, and external tailwinds from re-exports diminish but are partially replaced by investment, services expansion, and continued public spending.

An upside scenario could emerge if regional integration deepens, the Middle Corridor attracts high-quality investment, and productivity-enhancing reforms accelerate. A downside scenario would materialize if sanctions risks intensify, climate shocks worsen, or reform momentum stalls.

Progress on trade facilitation, incremental SOE reform, and renewable energy deployment would support stability, while the Middle Corridor gradually attracts higher transit volumes and logistics investment.

An upside scenario would materialize if regional cooperation deepens meaningfully and reform momentum accelerates. Faster implementation of competition policy, WTO-related reforms in Uzbekistan, improved water and energy coordination, and tangible cross-border integration in areas such as the Ferghana Valley could unlock productivity gains and crowd in higher-quality foreign direct investment.

In this scenario, Central Asia would move beyond transit and extraction toward light manufacturing, processing of critical minerals, agribusiness value chains, and export-oriented services, pushing growth closer to 6 % and strengthening job creation, particularly for youth and returning migrants.

A downside scenario remains plausible if geopolitical and structural risks intensify. Stricter sanctions enforcement affecting parallel trade, renewed volatility in Russia, sharper climate and water shocks, or reform fatigue could expose underlying vulnerabilities. Lower-income economies would be particularly affected through remittance channels, fiscal pressures, and exchange-rate stress, potentially dragging regional growth closer to 3-4 % and amplifying social and employment risks.

The strategic choice facing Central Asia in 2026 is therefore clear. Continued global attention provides an opportunity, but not a guarantee, of sustained prosperity. The countries of the region will need to leverage their renewed relevance to pursue deeper regional integration, harmonize rules and standards, and position Central Asia as a coherent economic space capable of absorbing higher-quality investment.

If successful, 2026 could mark the beginning of a transition from growth driven by external shocks and geopolitical arbitrage to growth anchored in productivity, skills, innovation, and regionally integrated value chains, turning Central Asia’s return to the global stage into a lasting economic transformation rather than a temporary moment of opportunity.

Central Asia remained one of the fastest-growing subregions globally

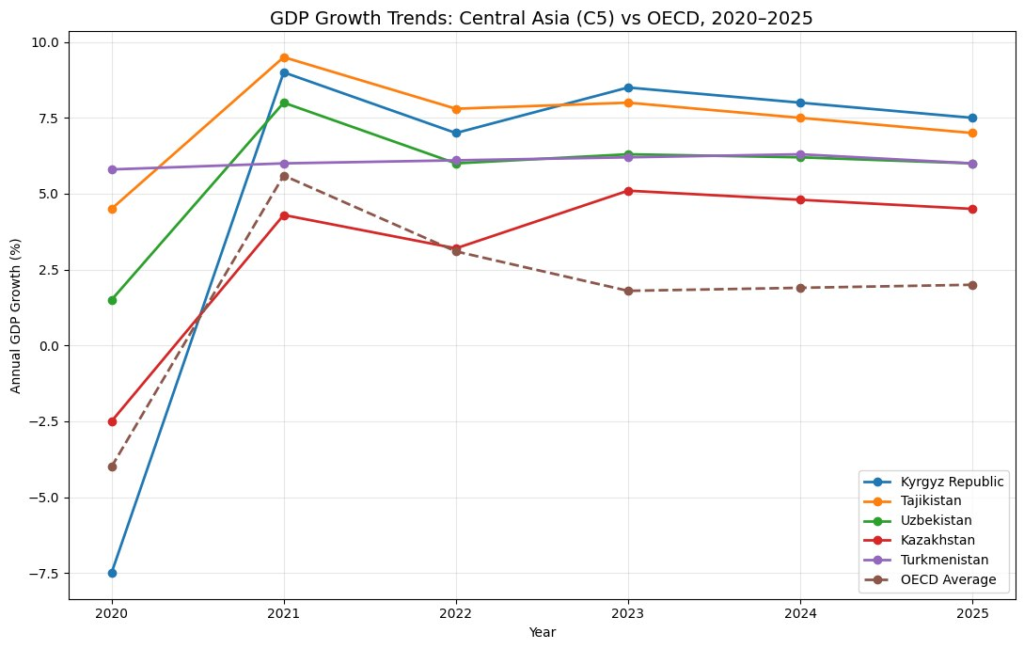

Economically, the year closed with strong headline performance. According to the World Bank’s Fall 2025 economic updates, Central Asia remained one of the fastest-growing subregions globally, with average growth in the range of 5 to 6 %. Kazakhstan benefited from hydrocarbons, metals, logistics, and public investment; Uzbekistan sustained momentum through domestic demand, construction, services, and reform-driven confidence; Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan recorded rapid growth fueled by remittances, trade, and services; and Turkmenistan continued to rely on gas exports and state-led investment.

Central Asia has recovered from the pandemic faster and more steadily than many advanced nations. While wealthier OECD countries are growing at about 2%, the five Central Asian economies are expected to grow between 4.5% and 7.5% in 2025. This shows strong economic energy, but the quality of this growth is still fragile.

The reasons for this growth vary by country and are often risky. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan rely heavily on services and money sent home by workers abroad. Uzbekistan is driven by local demand and market reforms. Kazakhstan depends on natural resources and investment, while Turkmenistan relies on government spending. To make this growth last, the region needs to create more private-sector jobs and protect itself from external shocks like climate change, price swings, and global political tension.

On the surface, 2025 appeared to confirm Central Asia’s resilience amid global uncertainty.

Yet the underlying drivers of growth revealed important vulnerabilities. A substantial share of recent expansion was linked to parallel trade, re-exports, transit services, and financial inflows associated with Russia’s economic reorientation.

While these dynamics supported short-term growth and fiscal revenues, they also exposed Central Asian economies to sanctions risks, reputational concerns, and potential volatility should enforcement tighten or trade patterns shift again.

The World Bank repeatedly warned that without stronger productivity growth, export diversification, and domestic value creation, current growth rates could prove fragile.

At the same time, 2025 marked meaningful progress on structural reforms. Several countries advanced market competition policies, reduced preferential treatment for state-linked firms, and strengthened antimonopoly frameworks, most visibly in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

State-owned enterprise reform moved forward unevenly but decisively, particularly in energy, transport, and banking, as governments sought to improve transparency, corporate governance, and fiscal risk management.

Tax administration reforms expanded digital filing and compliance tools, while early experimentation with artificial intelligence in public services and digital government signaled a longer-term shift toward efficiency and data-driven policymaking.

Trade policy and regional integration also gained momentum. Uzbekistan’s WTO accession process accelerated, anchoring customs reform, tariff rationalization, and regulatory alignment.

Critical Fronts of Growth

Across the region, governments invested in border facilitation, digital trade documentation, and logistics infrastructure, recognizing that competitiveness along alternative corridors depends as much on “soft” reforms as on physical infrastructure. These efforts aligned closely with the growing importance of the Trans-Caspian, or Middle Corridor, which in 2025 evolved from a strategic aspiration into a tangible priority for governments and investors alike.

Energy transition and climate resilience emerged as defining themes of the year. Investment in renewable energy expanded rapidly, especially solar and wind projects in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, supported by foreign investors and development finance institutions.

At the same time, water scarcity and climate stress became increasingly visible as binding constraints on agriculture, hydropower, and urban growth. Water governance and regional coordination, long politically sensitive, moved closer to the center of economic policy debates, underscoring the interconnected nature of climate, growth, and stability in Central Asia.

Labor markets and SMEs represented another critical front. Governments expanded SME support programs, improved access to finance, and simplified business procedures, yet informality and uneven enforcement continued to limit productivity gains. The return of migrants, partly driven by Russia’s economic slowdown, added urgency to job creation, skills recognition, and reintegration policies.

These returning workers brought experience, savings, and entrepreneurial potential, but also heightened pressure on local labor markets and social services if growth failed to generate sufficient quality employment.

The New Architecture of Regionalism

A defining structural shift in 2025 was the consolidation of the C5 consultative process as a credible mechanism for regional economic coordination and conflict resolution rather than a purely symbolic dialogue.

Regular meetings of Central Asian leaders increasingly focused on practical deliverables in trade facilitation, transport connectivity, water and energy coordination, and crisis-response mechanisms.

A historic milestone was the resolution of long-standing border disputes, particularly among Uzbekistan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan, including agreements on border demarcation in and around the Ferghana Valley, one of the region’s most densely populated and economically interlinked areas.

These agreements significantly reduced the risk of conflict, reopened border crossings, restored mobility for people and goods, and laid the foundation for cross-border trade, labor movement, and local economic integration. If sustained, the normalization of borders in the Ferghana Valley could transform the subregion into a cross-border hub for SMEs, agribusiness, light manufacturing, logistics, and services, leveraging dense population, shared value chains, and proximity to major regional markets.

Over time, deeper integration in the valley has the potential to generate scale economies, raise productivity, and anchor more inclusive growth across all three countries. Alongside border settlements, governments advanced commitments to simplify customs procedures, expand green corridors for agricultural trade, align digital border management systems, and coordinate infrastructure planning along key east–west and north–south routes.

While integration remains incomplete, the consultative process in 2025 delivered tangible outcomes that strengthened trust, lowered political friction, and signaled a decisive shift toward peace, openness, and regional interdependence as core economic assets.

Running in parallel, 2025 witnessed an unprecedented flurry of C5+ engagement formats, reflecting the growing desire of global powers to engage Central Asia as a single strategic market and geoeconomic corridor rather than five disconnected economies.

The most consequential milestone was the European Union–Central Asia Summit, which elevated relations to a strategic partnership and anchored the EU’s Global Gateway engagement in the region, including commitments linked to a €10 billion connectivity and investment package focused on transport corridors, energy, digital infrastructure, and critical raw materials.

The C5+1 Summit reinforced cooperation on supply-chain resilience, energy security, digital connectivity, and private-sector investment, translating into new initiatives supporting SME finance, trade facilitation, and critical-minerals value chains.

At the C5+Japan Summit, Japan committed to expanded cooperation on quality infrastructure, decarbonization, industrial upgrading, and human capital development, positioning Central Asia as a partner in resilient and sustainable supply chains.

Engagement with Russia through the C5+Russia Summit underscored continued economic interdependence in trade, labor, and energy, even as Central Asian countries actively diversified partnerships. China, Türkiye, and Gulf states simultaneously expanded financing, logistics, and industrial cooperation, confirming that the C5 format itself had become a preferred entry point for external actors seeking scale, predictability, and regional coherence.