Japan’s Break with “Silk Road Diplomacy” Signals a New Era of Resource Realism

The announcement of the first Japan–Central Asia Leaders’ Summit, to be convened in Tokyo in December 2025, represents more than a diplomatic milestone; it signals a fundamental restructuring of Tokyo’s Eurasian strategy. For over thirty years, Japan’s engagement was defined by “Silk Road Diplomacy,” a soft-power doctrine centered on cultural exchange, humanitarian aid, and gradual institutional support.

However, the volatile geopolitical landscape of 2025 has forced a pivot toward “Resource Realism.” Faced with fracturing global supply chains and an urgent need to secure non-Chinese sources of critical minerals, Tokyo is abandoning the passive, aid-based gradualism of the 1990s in favor of industrial integration.

This new era is defined not by donor-recipient dynamics, but by hard strategic interests: securing the tungsten, rare earths, and copper essential for Japan’s high-tech survival while offering Central Asia the capital and technology needed to escape geopolitical encirclement.

Decades of “Silk Road Diplomacy” Have Built the Foundation for a Strategic Pivot

Despite this sharp strategic pivot, the foundation for cooperation remains solid. Japan’s relations with the five Central Asian states did not begin with the massive trade volumes or politically charged alliances typical of other powers. Instead, they evolved through a gradual, intentional approach. The early vision of “Silk Road Diplomacy,” developed in the 1990s, positioned Japan as one of the first Asian powers to recognize the geopolitical significance of the newly independent republics. It articulated a strategy based on long-term stability, economic modernization, and human capital development.

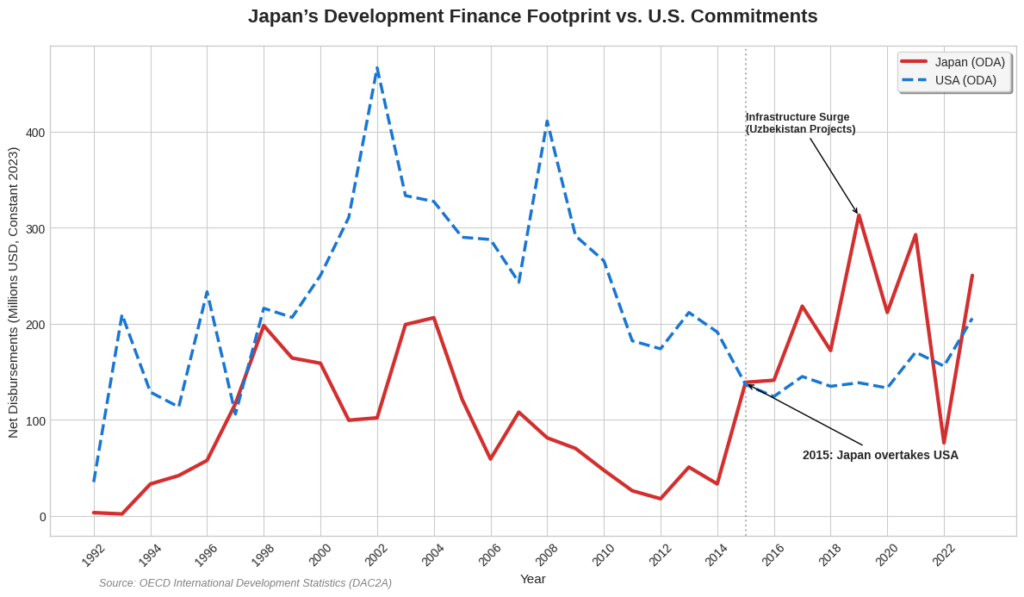

The trajectory of development assistance reveals often unnoticed comparative significance of Japan ODA to Central Asia. While the United States was the dominant donor during the early post-9/11 era (peaking at $466 million in 2002), Japan has effectively outpaced Washington as the primary source of ODA in Central Asia since 2015. In 2019 and 2021 alone, Japanese disbursements exceeded U.S. totals by nearly double (according to OECD ODA tracking data), driven largely by capital-intensive infrastructure loans in Uzbekistan.

These initiatives supported nation-building, public administration reforms, and the rehabilitation of critical transport and energy networks. The creation of the “Central Asia + Japan Dialogue” in 2004 formalized this trajectory, establishing a multilateral platform for sustained political dialogue. This mechanism has since become one of the region’s most enduring external partnerships, laying the groundwork for today’s more ambitious strategic vision.

Japan’s Reputation for Non-Interference Facilitates a Shift to High-Level Dialogue

Japan’s reputation across the region is defined by the consistency of its engagement. While other external powers often framed Central Asia through the lens of competition, spheres of influence, or purely extractive interests, Japan pursued a development-centered approach anchored in transparency and technical excellence. This foundation has generated an exceptionally positive image of Tokyo as a partner associated with high standards and non-interference.

Against this long historical arc, the December 2025 Summit represents the elevation of the relationship to a strategic level. The timing is critical. Central Asia is undergoing rapid transformation driven by economic diversification, demographic pressures, and shifting geopolitical alignments. Simultaneously, Japan is recalibrating its global partnerships to ensure secure supply chains and strengthen relationships in overlooked regions of Eurasia. The convergence of these agendas is now clearer than ever.

The current state of cooperation spans diplomatic, economic, and cultural dimensions. The Central Asia + Japan Dialogue remains one of the few mechanisms where the region interacts with a major Asian power on equitable terms. Japan’s diplomatic style, rooted in consensus-building rather than dominance, aims to cultivate regional stability and strengthen the capacity of Central Asian governments to pursue independent development paths. This political trust is a critical asset in an era of intensified Great Power competition in Eurasia.

High-Tech Infrastructure Offers a Developmental Alternative to Resource Extraction

Economically, while Japan’s total trade numbers may appear modest compared to China or the European Union, the developmental impact of its capital is disproportionately high. Japanese companies are active in the most strategic sectors of the regional economy, including energy infrastructure, advanced metallurgy, and logistics. Unlike investments that prioritize rapid resource extraction, Japan’s economic footprint emphasizes technology transfer, environmental standards, and long-term productivity.

JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) has played a transformative role across Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. Japan has funded major programs in transport infrastructure, hydropower rehabilitation, and digital governance. JICA’s operational style, emphasizing institutional strengthening and rigorous project management, has enabled Central Asian governments to internalize new skills and replicate methodologies beyond individual projects.

Key Sectoral Impacts:

Uzbekistan (Energy & Resilience): Japan has led energy sector modernization through partnerships with Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Marubeni, and JERA. These consortiums have upgraded major thermal power plants with modern combined-cycle gas turbine systems. The modernization of the Navoi power plant stands out as a success story, significantly increasing output efficiency while reducing emissions. Additionally, companies like Tokyo Rope have deployed advanced landslide protection technologies, addressing chronic infrastructure vulnerabilities in mountainous zones.

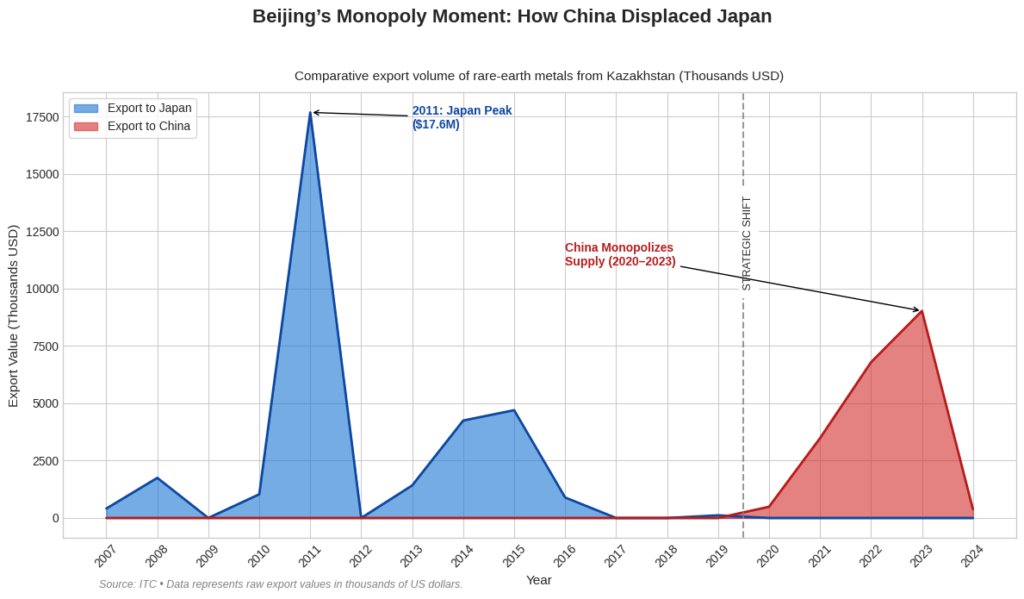

Kazakhstan (Critical Minerals & Industry): Japan has emerged as a strategic partner in mining technology and advanced metallurgy. Companies such as Sojitz, Sumitomo, and Toshiba have introduced cutting-edge processing systems that improve ore recovery rates and environmental safety. This is vital as Kazakhstan seeks to move up the value chain by processing rare earths, tungsten, and copper domestically. Japan’s involvement in hydrogen feasibility studies further positions Kazakhstan to integrate into future green value chains.

Kyrgyz Republic (Urban Resilience): Japan’s focus on disaster risk reduction has produced some of the most impactful interventions in the country’s history. Japanese-supported seismic retrofitting of public buildings in Bishkek, combined with engineering training, has significantly enhanced the capital’s preparedness for earthquakes.

Tajikistan & Turkmenistan: These nations have benefited from targeted expertise in hydropower rehabilitation, water management, and energy efficiency, filling critical gaps in climate adaptation and institutional development.

What makes Japanese investments particularly valuable is the systemic transformation they stimulate. By introducing higher standards in procurement transparency and engineering design, Japan fosters an environment where local firms can integrate into advanced industrial systems.

Investments in Human Capital Are Creating a Pro-Reform Administrative Class

One of Japan’s most durable strategic assets is its investment in human capital. Programs such as the Japan Development Scholarship (JDS), the Young Leaders’ Program (YLP), and long-term JICA training have educated thousands of civil servants, engineers, and economists from Central Asia.

These alumni now occupy influential positions in government ministries, central banks, and state-owned enterprises. Their exposure to Japanese governance norms, such as meritocracy, evidence-based policy, and ethical standards, complements ongoing reform efforts across the region. Unlike competitors who focus on physical infrastructure alone, Japan has helped cultivate a generation of reform-minded leaders whose professional networks continue to shape state modernization.

Tokyo Serves as a Critical Gateway to Western Alliances and the Indo-Pacific

The geopolitical ramifications of expanding cooperation with Japan are profound. Central Asian states are committed to multivector foreign policies, a doctrine designed to prevent overdependence on Russia or China. Japan’s role is uniquely important because Tokyo offers advanced technology and political neutrality without the coercive elements associated with other regional powers.

Crucially, Japan functions as a gateway to a larger ecosystem of global allies. Japan is a core anchor of the U.S.-Japan alliance and a key member of the Quad (alongside the US, Australia, and India). By deepening ties with Tokyo, Central Asian states indirectly enhance their ability to engage with this wider constellation of partners:

- The United States: Cooperation with Japan opens channels for dialogue on technology governance and supply chain resilience that align with U.S. interests.

- South Korea: As a close partner of Japan, South Korea’s expertise in battery production and AI-based industrial systems becomes more accessible.

- Australia: A leader in mining technology and climate adaptation, Australia’s engagement in the region is facilitated through Indo-Pacific frameworks championed by Tokyo.

- Southeast Asia: Japan’s deep business networks in Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam offer Central Asia opportunities to diversify trade beyond traditional Eurasian partners.

Japan’s focus on ethical sourcing and critical minerals (rare earths, tungsten) directly aligns with the regulatory ambitions of the US and EU. This cooperation helps integrate Central Asia into “trusted supply chains” that meet global standards, offering an alternative to environmentally harmful extraction methods.

Outlook: The Summit Must Codify the Shift from Aid to Industrial Integration

The region faces a narrowing window to modernize its economies before climate pressures and infrastructure obsolescence take hold. The Japan–Central Asia partnership is now at a decisive turning point.

- From Aid to Innovation: The relationship is shifting from traditional development assistance to joint innovation in AI, digital governance, and green energy.

- The Hydrogen Corridor: Japan considers hydrogen central to its decarbonization. Central Asia’s solar and wind potential could anchor joint hydrogen corridors connecting the region to Asian and European markets.

- Agri-Tech Solutions: With water scarcity worsening, Japanese innovations in irrigation efficiency and agricultural robotics will be critical for regional food security.

The December 2025 Summit in Tokyo offers the opportunity to codify this shift. Japan’s strengths, including advanced technology, transparent governance, and strong global alliances, align perfectly with Central Asia’s need for diversification. If successful, this partnership will not only accelerate economic transformation but also strengthen the region’s geopolitical autonomy, proving that Central Asia can be a bridge between the Euro-Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific.