To Stay Relevant, the C5+1 Must Act

In anticipation of the C5+1 tenth-anniversary summit in Washington, D.C., scheduled for November 6, 2025, following U.S. President Donald Trump’s invitation to Central Asian leaders, this moment provides a timely opportunity to take stock of the platform’s progress, challenges, and future prospects.

Over the past decade, the C5+1 has developed from a diplomatic experiment into a regular part of U.S.–Central Asia engagement, yet its path also teaches important lessons on how to make this partnership more pragmatic, balanced, and economically impactful moving forward.

Some future aspects of the C5+1 agenda were already discussed and strongly supported by Central Asian leaders during the recent visit of U.S. envoys Sergio Gor and Christopher Landau to the region, who highlighted a stronger, investment-driven partnership ahead of the Washington summit.

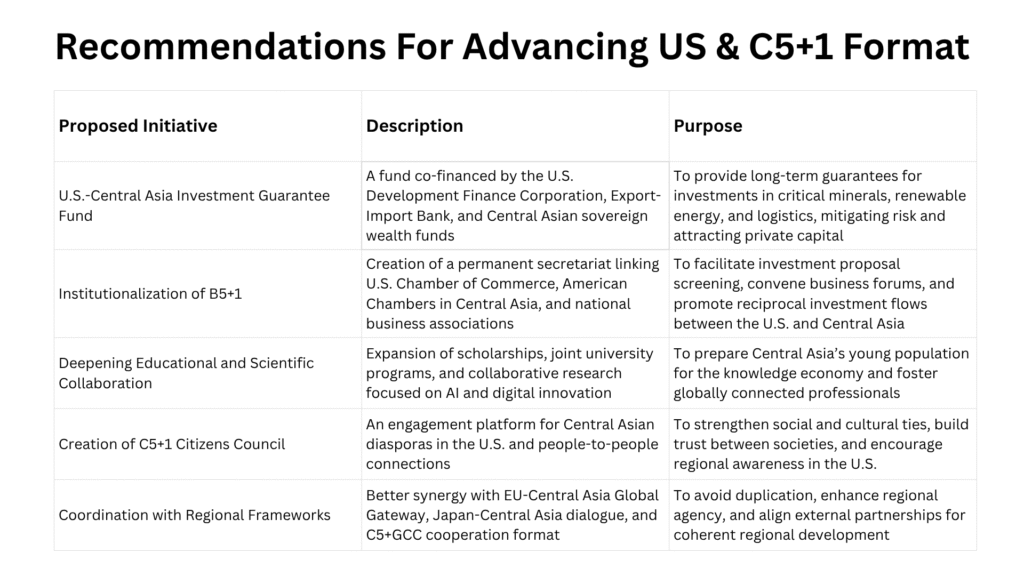

The table outlines recommendations for advancing the C5+ format in cooperation with the US and Central Asia. The recommendations are discussed in detail in the text below.

Three pillars of cooperation

When the United States and the five Central Asian republics launched the C5+1 diplomatic platform in Samarkand in November 2015, it was heralded as a milestone. The initiative, led by then–Secretary of State John Kerry, created the first structured mechanism for dialogue between Washington and Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Its founding declaration envisioned cooperation around three pillars—security, economic connectivity, and environmental sustainability—aimed at providing a collective platform for regional problem solving and U.S. engagement in a geopolitically sensitive neighborhood wedged between Russia, China, Iran, and Afghanistan.

Over the past decade, the C5+1 evolved gradually from ministerial meetings and ad hoc consultations to a more structured diplomatic format with thematic working groups and periodic gatherings of foreign ministers. The Biden Administration elevated its political standing by convening the first-ever C5+1 Leaders’ Summit in Washington in 2023, signaling renewed American interest in Central Asia’s stability, resilience, and connectivity.

The dialogue’s thematic scope expanded to include critical minerals, digital transformation, renewable energy, and climate resilience, while also touching on governance, gender, and inclusion. Yet despite this progress, the platform remained largely state-centric, revolving around foreign ministries and intergovernmental channels rather than opening doors to the private sector, investors, or broader society.

Quantity of C5+ Formats Doesn’t Equal Usefulness

The C5+1’s governance and institutional structure have remained modest, built around a few ministerial working groups co-chaired by the U.S. Department of State and the respective Central Asian foreign ministries. While these groups have produced valuable exchanges on trade, energy, environment, and security, they have lacked consistent follow-up mechanisms and long-term regional ownership.

Meetings were irregular, leadership rotated, and coordination often depended on U.S. initiative rather than regional demand. Unlike the European Union or ASEAN-type formats, there was no regional secretariat or technical body in Central Asia to ensure continuity and implementation.

This has fueled skepticism among Central Asian leaders about the proliferation of “Central Asia plus” dialogues that multiply without delivering tangible results.

President Emomali Rahmon of Tajikistan has pointedly observed that there is “an abundance of Central Asia plus formats that do not always serve the real needs of our countries,” stressing that what the region truly needs is pragmatic cooperation focused on infrastructure, industrial investment, and trade rather than rhetorical commitments.

Indeed, while U.S. initiatives under the Biden Administration on democracy, human rights, gender equality, climate action, and disability inclusion have aligned with global values and reflected Washington’s broader foreign policy priorities, they have not always matched Central Asia’s most urgent needs—namely, attracting foreign direct investment, gaining access to U.S. know-how and technology, and achieving the long-overdue repeal of the Jackson–Vanik amendment that continues to constrain trade normalization.

Weak Connection to the Business as a Major Limitation

One major limitation of the C5+1 framework has been its weak connection to the business community and its inability to mobilize significant private capital. For much of its existence, the platform operated primarily as a foreign policy dialogue rather than an investment mechanism. The notable exception came in March 2024, when the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), in partnership with regional chambers of commerce, launched the first-ever B5+1 Forum in Almaty.

This initiative created a parallel business track to complement the official diplomacy, gathering U.S. and Central Asian business leaders to discuss trade, energy, logistics, and critical minerals. However, this platform is still at an early stage and requires greater institutionalization, dedicated funding, and political backing from both sides to evolve into a true economic engine for regional cooperation.

As the C5+1 enters its second decade, it must pivot from dialogue to delivery. The next phase should be pragmatic, investment-driven, and mutually beneficial, reflecting both U.S. strategic interests and Central Asia’s developmental priorities. The geopolitical context has shifted dramatically since 2015.

War in Ukraine has disrupted traditional trade routes, China’s Belt and Road Initiative has reshaped regional infrastructure, and new players such as the Gulf states, Türkiye, and India are expanding their footprint in the region. In this crowded environment, U.S. engagement will remain relevant only if it delivers tangible economic partnerships, technological collaboration, and predictable investment flows.

Recommendation to Advance the C5+1 Format

One forward-looking proposal would be the creation of a U.S.–Central Asia Investment Guarantee Fund under the C5+1 umbrella, co-financed by the U.S. Development Finance Corporation, the Export–Import Bank, and Central Asian sovereign wealth funds. Such a fund could offer long-term guarantees for projects in critical minerals, renewable energy, and logistics—sectors that require patient capital and carry high political and market risks.

This would secure U.S. access to essential minerals such as tungsten, antimony, and rare earths, while enabling Central Asia to move up the value chain and create high-quality jobs. A stable financing mechanism of this kind would demonstrate that the C5+1 is not merely a forum for dialogue but a platform for action.

A second key step would be the institutionalization of the B5+1 through the creation of a permanent secretariat linking the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the American Chamber networks across Central Asia, and national business associations.

This body could solicit and screen investment proposals, convene annual business forums, and promote two-way investment flows. It should not only promote U.S. investments in Central Asia but also encourage Central Asian capital to invest in the United States, thereby strengthening reciprocity and trust.

Uzbekistan’s recent purchase of Boeing aircraft and Kazakhstan’s locomotive manufacturing deal with a U.S. company are promising examples of emerging commercial partnerships through Central Asian investments in the U.S. that create jobs on both sides. Both deals received high praise and were personally welcomed by President Trump.

Equally important is the growing contribution of Central Asians to the U.S. economy and society. The region’s entrepreneurs and professionals are proving to be highly innovative, industrious, and adaptable—legally integrating into and enriching the fabric of America’s multicultural economy.

The Uzbek diaspora, one of the fastest-growing in the United States, has become a vibrant example of this trend. Through small business expansion, hospitality ventures, and cultural entrepreneurship—including several Uzbek restaurants now featured in the Michelin Guide—they exemplify how Central Asian talent contributes to American economic vitality and cultural diversity.

Beyond trade and investment, the renewed C5+1 agenda should deepen educational and scientific collaboration to prepare for the knowledge economy of the future, particularly by leveraging U.S. expertise in artificial intelligence and digital innovation. Central Asia’s young population represents a demographic advantage, but its long-term prosperity will depend on education, digital literacy, and exposure to cutting-edge technologies.

Expanding U.S.–Central Asia partnerships through scholarships, joint university programs, and collaborative research would strengthen human capital, foster a new generation of globally connected professionals, and build enduring trust between societies. Therefore, the C5+1 can also play a practical role in enhancing people-to-people connections by creating a C5+1 Citizens Council and engaging more actively with Central Asian diasporas in the United States, while encouraging Central Asians to involve and connect more Americans across the region.

C5+1 must find better synergy with other regional frameworks

Finally, the C5+1 must find better synergy with other regional frameworks such as the EU–Central Asia Global Gateway, the Japan–Central Asia dialogue, and the C5+GCC cooperation format. Coordination among these initiatives would avoid duplication and demonstrate respect for regional agency, ensuring that external partnerships complement rather than compete with each other.

After a decade of cautious experimentation, the C5+1 stands at a crossroads. It has succeeded in keeping the United States meaningfully engaged in Central Asia, but it now needs to mature into a results-oriented partnership that prioritizes investment, innovation, and education.

By anchoring its future in concrete initiatives such as an investment guarantee fund, a joint B5+1 secretariat, and deeper educational exchanges, the platform can move beyond diplomacy toward durable economic and social impact. In doing so, it will make both the United States and Central Asia safer, stronger, and more prosperous—united by the shared logic of pragmatic diplomacy that delivers mutual gain in an increasingly uncertain world.